What empty houses tell

DOI: 10.60650/emptiness-5cs8-an10

May 2023, Suceava county, Romania. One misty morning, in a Hutsul village near the Ukrainian border, 72-year-old Parascha tells me: “Fortunately we’re here, and you’re here too, because with this fog, one feels all alone in the world. If we weren’t here, this place would be pustiu,[1]I focus on Romanian terms since this is my primary fieldwork language, including among Hutsuls whose mother tongue is a Ukrainian dialect. a desert”. Parascha and her husband Orest live in one of the last farmhouses inhabited year-round in this mountainous settlement. At times, one does feel marooned like on a deserted island, especially since accessing basic amenities requires either a three-hour hike or a rollercoaster ride over potholed roads and rickety bridges.

Pustiu, which in Romanian refers to landscapes empty of human presence, is one metaphor locals use to articulate their changing territorial realities. In fact, my observations in the two borderland communities – Hutsuls of Romania, and Romanians of Ukraine – where I conducted fieldwork (2022-25) echo Dace Dzenovska’s and the EMPTINESS team’s research on emptiness as a socio-spatial configuration (Dzenovska et al. 2025). For both places, time and place broke after socialism’s fall: după Revoluție (‘after the Revolution’) in Romania, and după Soyuzul (‘after the Union’) in Ukraine. Post-1989 market liberalisation rendered marginal Carpathian animal husbandry uncompetitive whilst local state enterprises collapsed. From the 2000s, limited opportunities drove massive labour migration to Western Europe, intensifying after Romania joined the EU in 2007. Villages began losing population seasonally or permanently. On the Ukrainian side, Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion created new dispersal dynamics.

Among the many ways I could engage with this ‘portable analytic’, I focus here on interactions with the ‘empty’ built environment. Both communities deploy narratives entangling absence, people, place, and vitality around case goale, ‘empty houses’, ubiquitous in their villages. However, despite their proximity – about 30 km apart – diverging histories shape distinct experiences and temporalities of emptiness.

Empty houses that rot

Walking past abandoned dwellings, Parascha and Orest tell stories about their former inhabitants before concluding: “Soon our house will rot (va putrezi) like these empty houses”. When elderly residents die, heirs rarely take over their farmhouse, choosing instead the comfort of valleys over the remote heights. Many let the houses crumble rather than sell them due to a visceral attachment to land ownership and, some say, to their parents’ memory.

Such houses expose Parascha and Orest’s anxiety about legacy, alongside disappointment with their children who show diminishing interest in the place. The couple notice how even their urban daughters’ bodies have become unaccustomed to the rural lifestyle: their hands can no longer milk cows, their stomachs can no longer digest homemade dairy, their tongues can no longer pronounce Hutsul. This corporeal estrangement excludes descendants from a place their parents fully identify with.

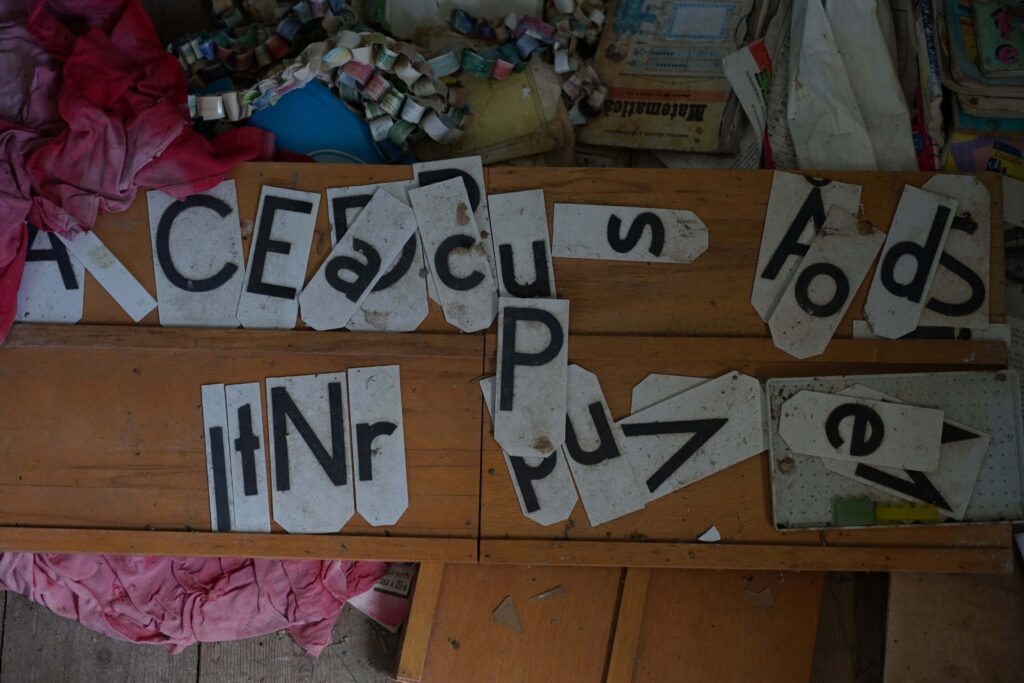

Discourses on empty houses connect to interactions with other decaying structures. When Parascha showed me the abandoned school facing their farm, her daughters reproached her for giving visitors poor impressions of the place. She retorted: “We did not do that, it’s the thieves who govern us”. After the school’s closure in 2010, the couple installed new roofing to prevent rain damage, hoping it would be reused as a guesthouse or a museum. Yet the school “remains like that” because municipal councillors, “who only visit before elections”, made no decisions about its demolition or sale. Like the failing infrastructure mentioned earlier, the school’s interior mirrors the institutional neglect decomposing the village. State inertia creates a vicious circle where depopulation makes public investment seemingly pointless, thereby accelerating further emptying.

Parascha and Orest’s sense of responsibility extend to other communal structures they participated in building and maintaining throughout their lives. They clean the chapel, mow its cemetery, and light candles on graves as fewer descendants visit each year. One spring, while repairing fences, Parascha chuckled: “We’re like fences engulfed by brambles (garduri în mărăcină), old, but still here”. This analogy captures both resignation and endurance as they identify with the place’s decay; yet as keepers of communal buildings’ keys and neighbouring empty houses, they hold the place together. Place maintenance offers them purpose and pride, resisting while they still can the village’s absorption into the ‘wilderness’ (another translation for pustiu) despite their pessimism about its fate. This is why Parascha repainted their house’s façade in a bright yellow that spring: “An unkempt house looks bad, like these empty houses. We’re visible to passers-by, we maintain ours so they see we’re alive!”.

Nostalgia doesn’t preclude openness to other futures. Locals welcome any presence that dissipates pustiu and counters rotting, be it farmers from the valley using absent owners’ field or ‘foreigners’ buying old houses for tourism: “At least, they bring some life back to this place”.

Empty houses that sleep

January 2024, a Romanian-speaking village in Chernivtsi region, Ukraine. 41-year old Lena has returned from Italy, where she works as a caregiver like many women here, for winter festivities. This seasonal homecoming briefly reunites scattered migration paths before they diverge again. Since 2022, many men of fighting age have vanished with their families, leaving behind half-empty classrooms and darker nocturnal landscapes. Walking through her neighbourhood, Lena remarks: “Before 2022, all the houses had Christmas lights. Now everything’s dark. Our parents’ generation lived 15 in a house with two rooms. Now, houses are huge but empty”. Here, case goale refers to houses awaiting their absent owners’ return.

The village landscape is contradictory. Derelict kolkhoz and timber factory buildings never fail to elicit head-shaking from interlocutors over the age of 50, who lament the place’s decline. Yet in 2025, the mayor claimed ‘city’ status (misto, Ukrainian) based on 10,444 registered inhabitants, while economic vitality appears to flourish through ostentatious ‘palace halls’ – some funded by border trafficking, rumours say – and uncanny alleys of identical villas lining roadsides. Looking closer, the structures seem lifeless and many houses are still under construction.

This phenomenon is common across the border throughout the Romanian countryside, even inspiring cultural production. Emigrants sustain emptiness from afar, maintaining houses through relatives in the village. These unfinished villas materialise tensions between dreams of building one’s ideal household at home and the impossible economic conditions for return (Moisa 2020). Their invasive presence somehow compensate for their owners’ never-ending absence.

In post-2022 Ukraine, empty houses tell another story. Local Facebook groups feature discounted villa sales, suggesting owners won’t be coming back. Others ask villagers to care for their dwellings as they watch how the conflict unfolds. When Lena returns home, typically for two months every quarter, she tends her cousin’s house. During winter, she regularly lights the woodstove to prevent frost damage and humidity, and hosts ritual visits on her cousin’s behalf. On ‘old’ New Year’s Eve (13 January), she receives Malanka, a group of masked youth performing songs and dances in each courtyard, wishing each household prosperity. On 19 January, Epiphany’s day, she welcomes the Orthodox priest who blesses each house with holy water. These local winter traditions, as they bring hope for the coming year, reintegrate empty houses and their owners into the social fabric. The processions of residents, walking door-to-door throughout the hamlets, ritually enact the village’s unity and re-densify the place.

These empty houses do not rot, they ‘sleep’ (dorm), as I heard several times. Through basic upkeep and annual blessings, they are artificially maintained into a dormant state that embodies suspended – due to uncertainty brought by war – rather than extinguished vitality.

Desert(ificat)ion

Discourses around ‘empty houses’ frame place as a living organism through analogies between matter and residents’ trajectories. Caused by neglect, a place’s emptiness is experienced as terminal decline, or as an indefinite liminality when it is sustained by minimal care. The absent – locals or authorities – are perceived as active agents of such process, which result from status quo.

Matter mediates how locals sequence ‘place-unmaking’ through temporal ruptures, whether socialism’s fall, EU integration, or military invasion, that create or reinforce unequal power relations. Emptiness narratives express feelings of injustice, marginalisation, and disqualification, and question individual and collective values and belonging.

Elderly Hutsuls identify ‘democracy’ as the main desertifying force making their lifetime’s work obsolete through market competition: “People leave because our milk is not needed anymore”. Yet they admit a certain irony. Ceaușescu’s systematisation plan would have emptied Hutsul villages anyway, relocating people to towns in order to reserve the mountains for industrial livestock grazing: “If there hadn’t been the Revolution, we would have been expelled from here”. Meanwhile, many Romanian Ukrainians identify war and mobilisation as breaking points transforming seasonal absence into desertion, in response to long-standing felt discrimination from the authorities.

Emptiness disrupts social order and unveils multifold relations to place. In the Hutsul village, absent owners trouble customary land use, profiting from EU subsidies without farming and getting into conflict with villagers whose cows trespass their unfenced properties. Across the border, wartime emptiness exposes moral economies based on family loyalty over national allegiance.

Despite deploring their living conditions in deserted settings, my hosts also want to ensure I understand how much their place matters. In Ukraine, 55-year-old Vasile drives me through the village’s centre to another hamlet. After explaining how everything went bad after the USSR’s collapse, he concludes, as we part: “But don’t forget to tell people that our village is a small corner of Heaven on Earth”.

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the CC-BY (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International) licence, which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | I focus on Romanian terms since this is my primary fieldwork language, including among Hutsuls whose mother tongue is a Ukrainian dialect. |

|---|