Soviet debris: failure and the leftovers of construction

DOI: 10.60650/EMPTINESS-P455-4X20

“Just three hundred people – and what a dump!”

Russian anthropologist Nikolai Ssorin-Chaikov records the bewildered yet unconcerned observation of an Evenki reindeer herder as he surveys the accumulated rubbish that surrounds Katonga, a remote Siberian settlement dating back to imperial times. Katonga’s inhabitants have witnessed the ebb and flow of ‘development’, from the foundation of the settlement through the Soviet era when the planners of the socialist order promised them a ‘better future’. What different progress might the ‘gift of socialist modernity’ have brought to this outpost of remoteness, why did it fail to deliver, was it indeed a failure, and what is its aftermath? What space might exist within modernity’s tight weft of discipline and instrumental rationality, for the undisciplined, the irresponsible, and the indocile? These are questions that Ssorin-Chaikov’s work raises.

The blog post below, which speculates upon the ‘before’ and ‘after’ of the Soviet metanarrative, is refashioned from an article that Ssorin-Chaikov first published five years ago. It is based on fieldwork dating back to the 1980s. The exploration of failure, ruin, and emptiness in socialist and postsocialist sites long predates our EMPTINESS project. This blog post highlights the longstanding interest taken by anthropologists in the marginal, the unsuccessful, the flotsam and jetsam of history and of socialist modernity. Our project will attempt to connect with the archive of this work across the former socialist space and more widely.

The EMPTINESS project is establishing a relationship with the Social Anthropology Division of the Higher School of Economics in St Petersburg, which is headed by Dr Ssorin-Chaikov. We plan that this initiative will facilitate scholarly exchange and joint seminars. We are looking forward to a fruitful collaboration.

Dominic Martin

Soviet debris: failure and the leftovers of construction

“The first sign of civilization is the dirt of your boots,” said Vas’ka, an Evenki hunter and reindeer herder in his late 20s. We were en route, in the summer of 1994, from a forest camp to a northern Siberian village that I call Katonga. He pointed to wheel tracks that were visible on an otherwise impeccably green pathway. Dirt appears when a truck breaks the grass and the moss. If you are traveling by foot from an area where trucks don’t go and nomadic camps are interconnected through reindeer passes, this gradually appearing dirt means that you have entered truck territory and that ‘civilization’ – that is, the village – is within a day’s walk. The road widened and slowly became solid as soft moss gave way to wheel tracks. “The second sign [of civilization] is drops of gasoline in a road puddle,” Vas’ka noted. It was no longer possible to drink from puddles as it had been further back, when they contained fresh and clean ice water. There is permafrost underneath the moss. As we continued to walk, occasional garbage dumps appeared along the road, multiplying into huge piles and endless rows in the last 15 kilometers or so from the village. The roadsides are the village’s dumping ground and sewer. Rusting food cans and broken glass bottles were in and between the dumps. The newest deposits were sawdust from the collective-farm sawmill, emanating the smell of fresh wood, mixed with the rot of household and office waste. The sound of the sawmill greets you once the village is within sight. Puddles become knee-deep and swampy as the road turns into a village street. Some of these streets have wooden sidewalks. Older huts intermix with new houses and a couple of half-finished three-story apartment blocks. All is wooden, and the village is littered with the leftovers of construction. The schoolhouse is surrounded by scaffolding. Vas’ka laughs: “It’s amazing, just three hundred people – and what a dump!”

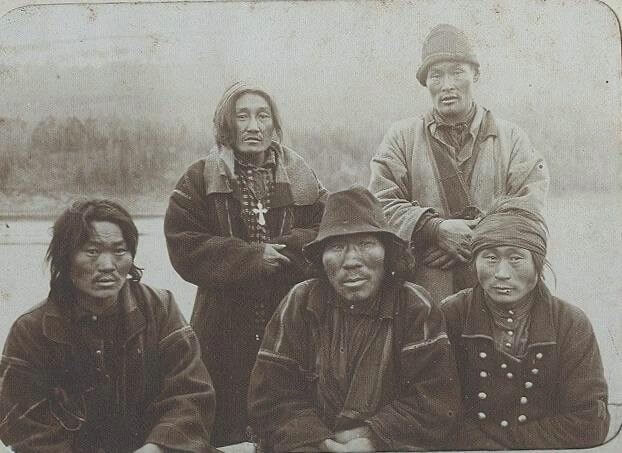

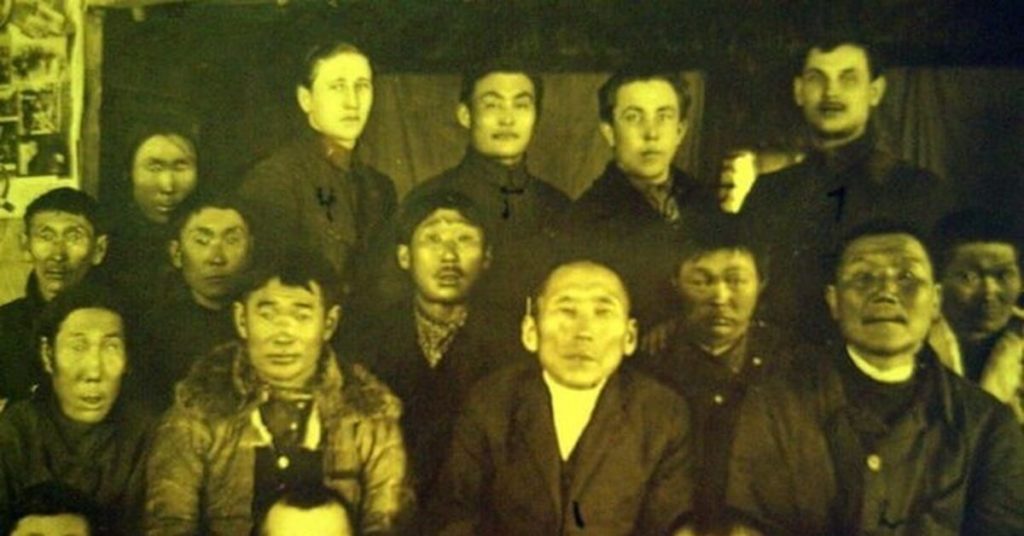

Katonga, in addition to its dumping grounds, had accumulated the debris of multiple Soviet projects as it grew from a tiny trading post of imperial Russia. It is located on the banks of the Podkamennaia Tunguska, the ‘Stony River of the Tungus’, the northern tributary of the Yenosei river, in Krasnoiarsk province. The ‘Tungus’ is the Russian colonial name of the Evenki, and ‘stony’ refers of the rapids that make most villages on the upper part of this river inaccessible by cargo boat for most of the short summer. Katonga was part of a rarified network of outposts where a ‘better future’ for Siberian indigenous peoples was to be built and where the socialist organization of work, as well as schools, hospitals, veterinary science, hygiene, and other marks of ‘civilization’, were brought to the ‘backward’ and the ‘nonmodern’. This is what I elsewhere call the gift of modernity, a Soviet civilizing mission that was abruptly abandoned after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In those parts of northern Siberia that were spared from oil and gas resourcing, this construction included the collectivization and sedentarization of nomadic hunters and herders, schooling, periodic campaigns to limit the consumption of alcohol, etc. Most of these were not quite success stories, and the failure of such projects was not the exception but the norm. As Vas’ka’s father Vladimir said to me once, describing his long Soviet career: “We are always busy building something and always live in an unfinished building. Who knows, however, what we build, and where we live!” This is clearly a lasting condition, but it is not clear whether such unfinished construction is not yet completed or already a ruin.

If this was a construction road, ‘the path of noncapitalist development’, it was both paved with and enabled by the debris of otherness. The road to an indigenous ‘better future’ was paved with failures. If the village was a “dump” of their material remains – byproducts of inefficiencies and poor planning – it is also a monument to abandoned projects in social constructivism. The accumulative goal of these various projects was to achieve progress from ‘primitive’ to ‘scientific’ communism, or at least to approximate a standard Soviet model of economy and society. But the result was an indigenous underclass and new hunting-gathering lifestyles that included Soviet welfare opportunism and often took the debris and infrastructure of these very developmental projects as targets of foraging.

Socialism, here as elsewhere in the former Soviet bloc, looked different in reality from how it looked on paper. The Katonga collective farm director told me in 1989:

I hire newcomers for the village construction because if I created an Evenki construction team, they would not show up for work, no matter how much I pay them. They will tell me: “I went hunting”, or “I went to pick berries instead”. Or they would not show up on time. They lack discipline [im ne khvataet discipliny]. But what do you expect? No matter how long you feed the wolf, it still looks back to the forest.

In his last remark, he cited a Russian proverb about the inner qualities of people, rather than wolves. These idioms of wildness recast the poetics of unfinished construction as a state of nature in which failure highlights the limits but also the necessity for the state and its civilizing mission, which is transformed from the Soviet back into the imperial. Here, fragments of the imperial imagination both undo the Soviet project and perpetuate it on a par with the otherness that is produced by the Soviet reforms and their failures.

One of the affirmations of the neoliberal view of modernity was an acknowledgement that its geopolitical competitor, Soviet-style state socialism, was an historical error. It failed because it was rooted in erroneously conceived human nature and in erroneously conceived types of economy and polity. No matter if it confirmed Ronald Reagan’s label of ‘evil empire’, the issue was its foundational theoretical mistakes, with chronic failures being their consequence. Winston Churchill remarked in a 1948 political speech that ‘socialism is the philosophy of failure’.

But the anthropological approach to socialism started from an inverse thesis: Soviet-style socialism was not an historical error but a social and cultural reality like any other. It could not be understood by taking capitalist modernity for granted as modernity’s ‘normal’ condition. Socialist inefficiencies and failures were rethought in terms of socialism’s internal cultural logics. James Scott (1998), reflecting on the ‘great historical confidence in progress’, argues that it is modernity that in fact fails in its universal drive to construct modes of existence around its imperative of clarity (‘legibility’) and efficiency. In contrast, James Ferguson (1994: 252, 255-6) submits that failure is paradoxically functional with modernity’s very logic. Failures are not ‘side effects’ of well-intentioned developmental projects, but rather Foucauldian ‘instrument effects’ that are instruments of the exercise of power. The Siberian example of Katonga is a microcosm of Soviet-style developmental modernity, which not only resonates with both Scott’s and Ferguson’s perspectives, but also highlights the way in which its ideology of ‘noncapitalist development’, of which Siberia was one of the exemplary contexts, was conceived as an explicit alternative to the linearity and inevitability of capitalist modernization.

When Vas’ka commented en route from the forest to Katonga that the village was “…just three hundred people – and what a dump!” his voice and intonation conveyed no surprise or irritation. This was business as usual, as it had been since his childhood. His irony had a finality of judgment. But I was once struck by a very different narrative of arrival in Katonga. In 1989, I was traveling there for the first time, coming by river from the regional center Baikit. A Russian district inspector offered me a motorboat ride with him after we had a long conversation in Baikit about indigenous development. “It is amazing that the Evenki still shelter in tents,” he remarked when he learned that I intended to do fieldwork in the forest. “We really should do something about this.” He marveled at the ‘Stony River of the Tungus’, with its spectacular rocky bed. “What primordial beauty [pervozdannaia krasota],” he exclaimed. Then we arrived and saw half-built houses, dirty unpaved roads, garbage, and mounds of sawdust. It became apparent from his remarks that most of these features of the village were actually not new to him. But his reaction was that, however lasting, these were signs of a beginning: “The first furrow of civilization,” he said with a smile. While Vas’ka articulated a spatial perspective on such debris, this inspector’s comments were temporal. This disorder of half-constructed villages was temporary. It was a beginning of civilization on the ‘river of the Tungus’, with many of these Tungus ‘still’ living in tents. This disorder marked the aesthetics of the Soviet order as not-yet-fully there.

These different perspectives highlight different ways in which the history of Soviet order is written from its metanarrative, which breaks down the historical chronology into a foundational binary distinction of ‘before’ and ‘after’. These perspectives illuminate how relational or situated this temporal boundary is. It is drawn differently at different points of the complex social space of Soviet reforms. Yet they also prompt questions of what exactly this ‘before’ is and what exactly situates it on the other side of the ‘now’. What makes it something other than Soviet? Exactly what constitutes this otherness?

Nikolai Ssorin-Chaikov

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the CC-BY (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International) licence, which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.