RE/MEMORY

“RE/MEMORY” by Ian McNaught Davis was one of four works featured in the online Art Exhibition for the “Emptiness: Ways of Seeing” conference, held on 30 September 2021. All words and photographs below are by the artist.

* * * * * *

My project is an exploration of the liminal space through the medium of analogue photography.

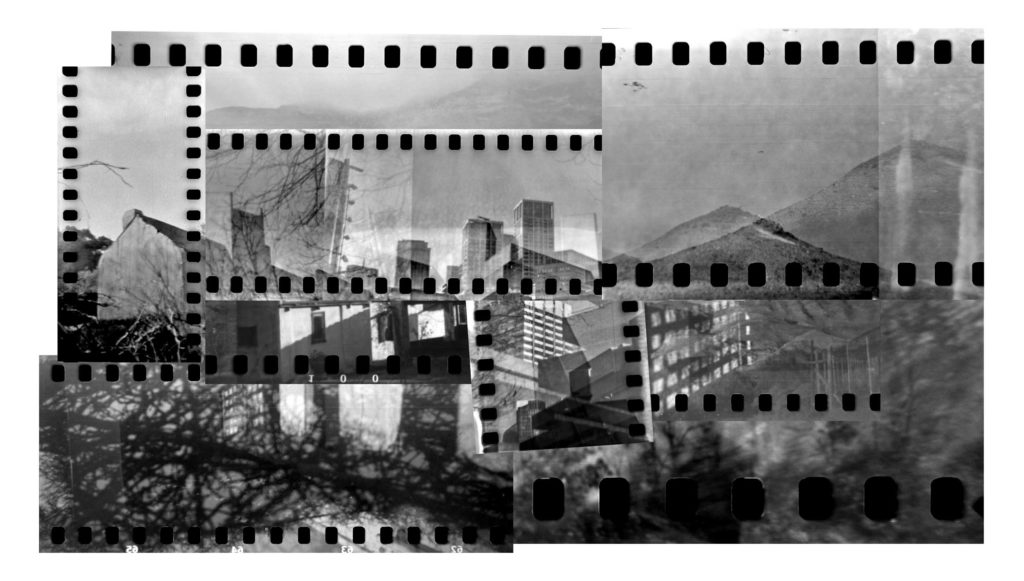

Through hand-developing film negatives and collaging the subsequent images, I have built imaginary landscapes that show the interplay between man-made objects and nature sharing the same space.

I worked as a photojournalist in Georgia for two years, where I covered assignments in former Soviet countries, including Kazakhstan, Armenia, Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan.

Like many foreigners, I was drawn to these visually arresting scenes of the past. I became fascinated with the physical remnants of the communist era: abandoned hotels, disfigured statues, aging mosaics. Initially my work focused on entropy in a more superficial sense: photographing ruins for the sake of photographing the drama of dereliction.

Over time, I became more interested in the interplay between man-made buildings and the natural realm. I became drawn to the tension between these forces – the sense of buildings relinquishing their dominion and nature encroaching amidst this – together in a spatial limbo.

Above is an abandoned tea factory in the town of Tsalenjikha in the subtropical region of western Georgia. In 1985, Georgia was the top producer of tea in the Soviet Union.

Through photographing the presence of nature in scenes like this, I learned to see that emptiness is not always a finite endpoint but it could also mark a transition to another state beyond abandonment or dereliction.

In this particular scene, I could see the complexities of the situation – that the sense of emptiness isn’t just a reminder of ambitious ideals gone bad, but also the promise of fresh grass for cattle. Emptiness can hold feelings of decomposition and of gestation in the same space.

The steel and concrete manifestations of humans that blend with the stubborn vitality of nature gives rise to a sense of liminal space: a transition between two states of being.

I’ve explored the idea of liminal space through the writings of Professor Jeff Malpas of the University of Tasmania. In his essay The Threshold of The World, he writes that the liminal is “that which stands between, but in standing between it does not mark some point of rest”.

These are spaces, he says, that are “characterised by dynamis than energeia”.

And in building these imaginary landscapes, I want to emphasise the plausibility and potency within these spaces.

This ambiguous state of betwixt and between is embodied by Janus – the Ancient Roman god of beginnings, ends and transitions. This puts forward a question: how different are these three concepts from each other?

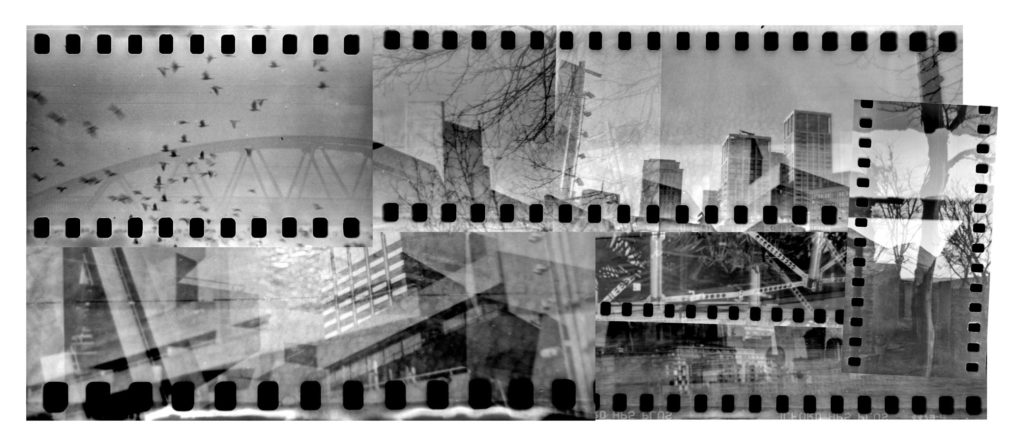

Initially I began my project of showing liminal space through using the technique of double exposure, whereby I’d shoot two scenes without winding the film on in my camera in order to get two different elements stamped onto each other.

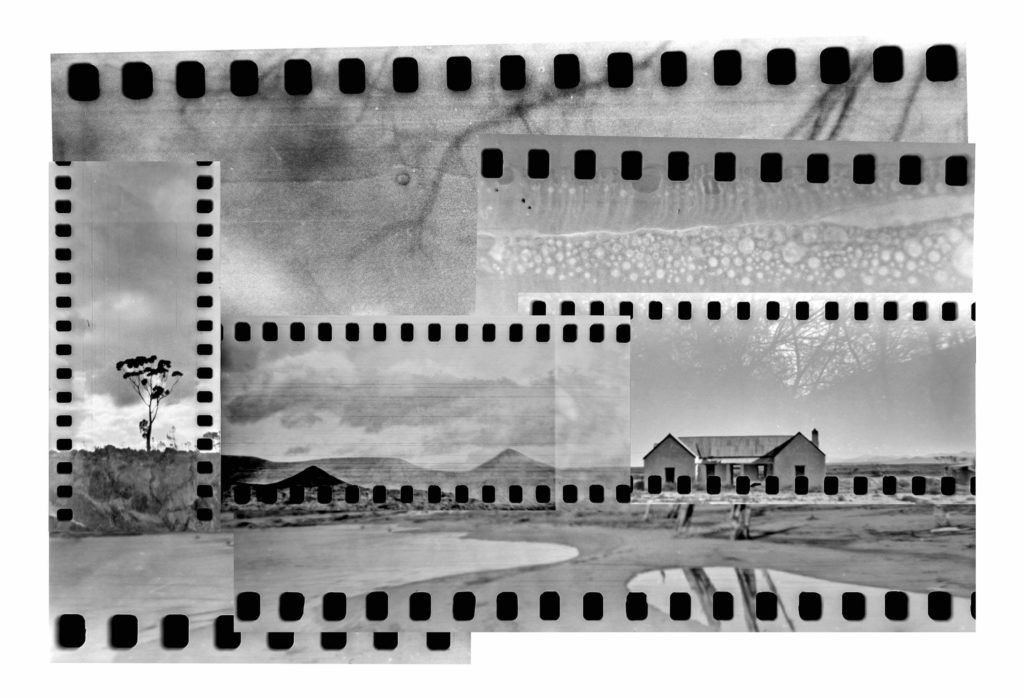

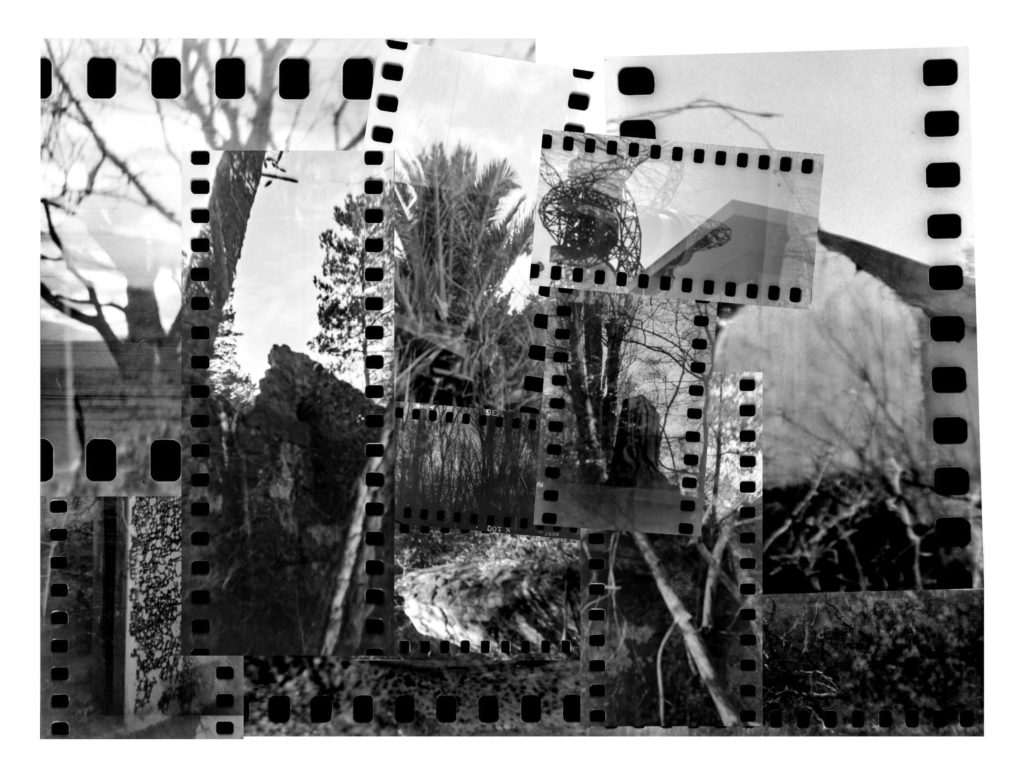

Above is a scene of an abandoned house shot in the Karoo, a vast, semi-arid region of South Africa, superimposed against an image of branches from a nearby bush.

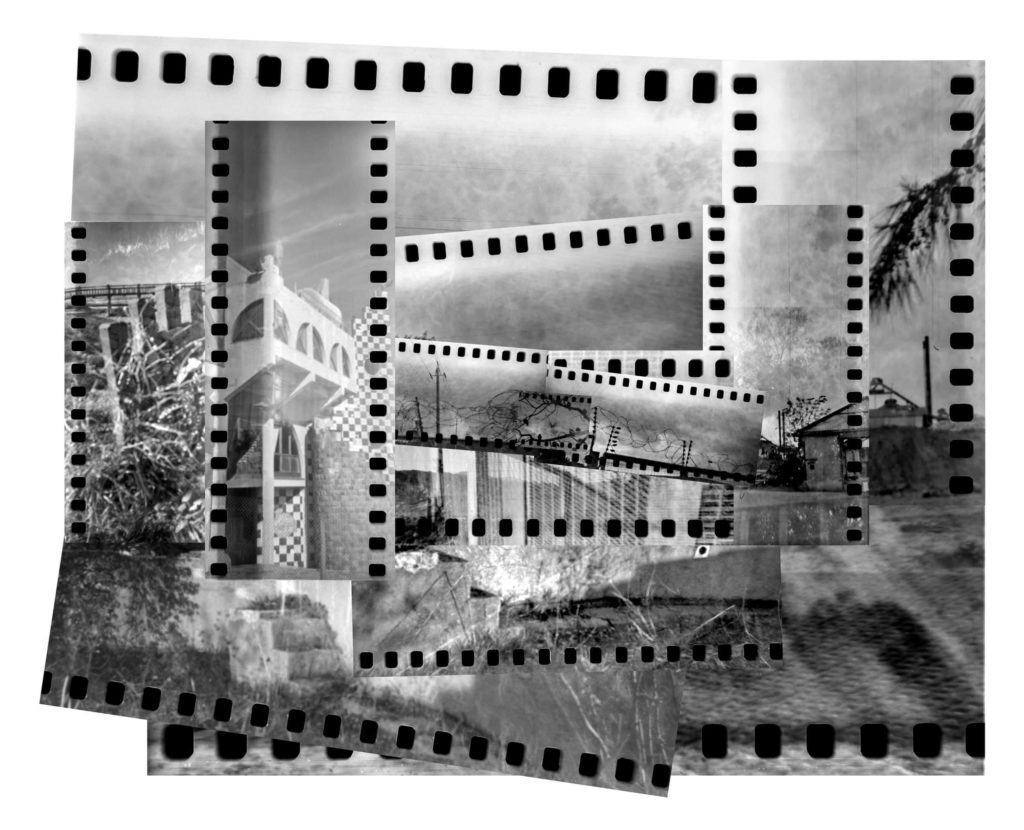

This double exposure was shot in Stratford, London of remnants of art outside a stadium from the 2012 Olympics and then exposed against the trees alongside a river.

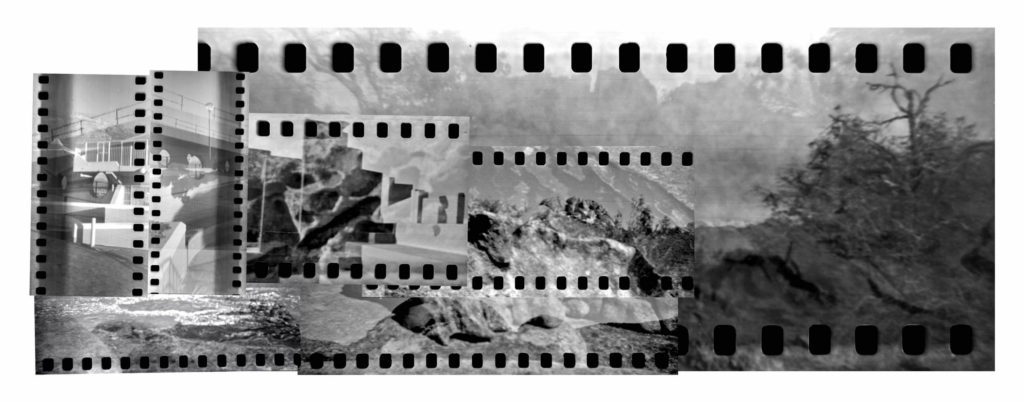

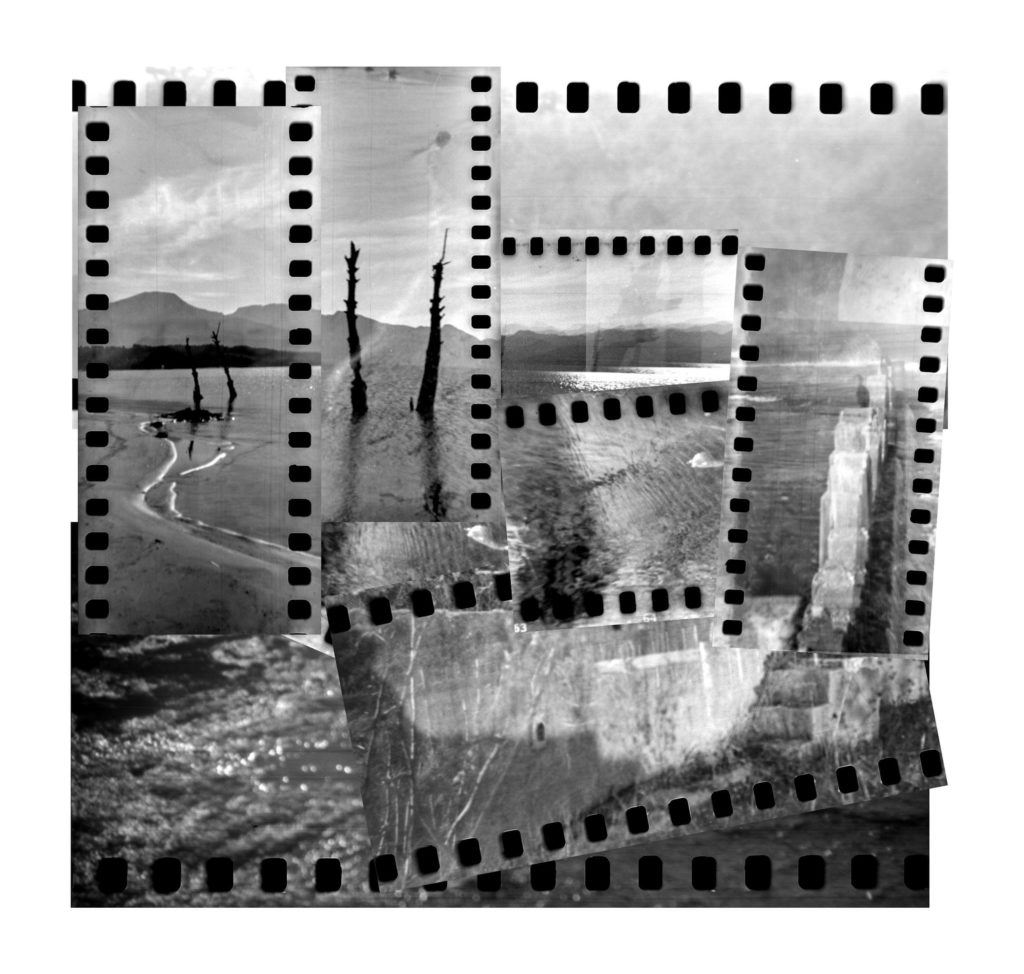

But in order to add nuance to the tension between the artificial and the organic, and to create more of a sense of space than just showing two contrasting subjects, I decided to arrange multiple double exposures into collages to create fictional landscapes.

The images were shot in London and throughout South Africa. Since film developer is difficult and expensive to get hold of in South Africa, I was able to develop my negatives in a concoction of instant coffee, Vitamin C tablets, pool cleaner and salt.

Diverging from my documentary photojournalism work that was centred on photographing people, I’ve shifted towards making pictures of trees on analogue formats.

The darkroom is especially relevant to the concept of liminal space – with its chemically induced gestation period – and so too are trees.

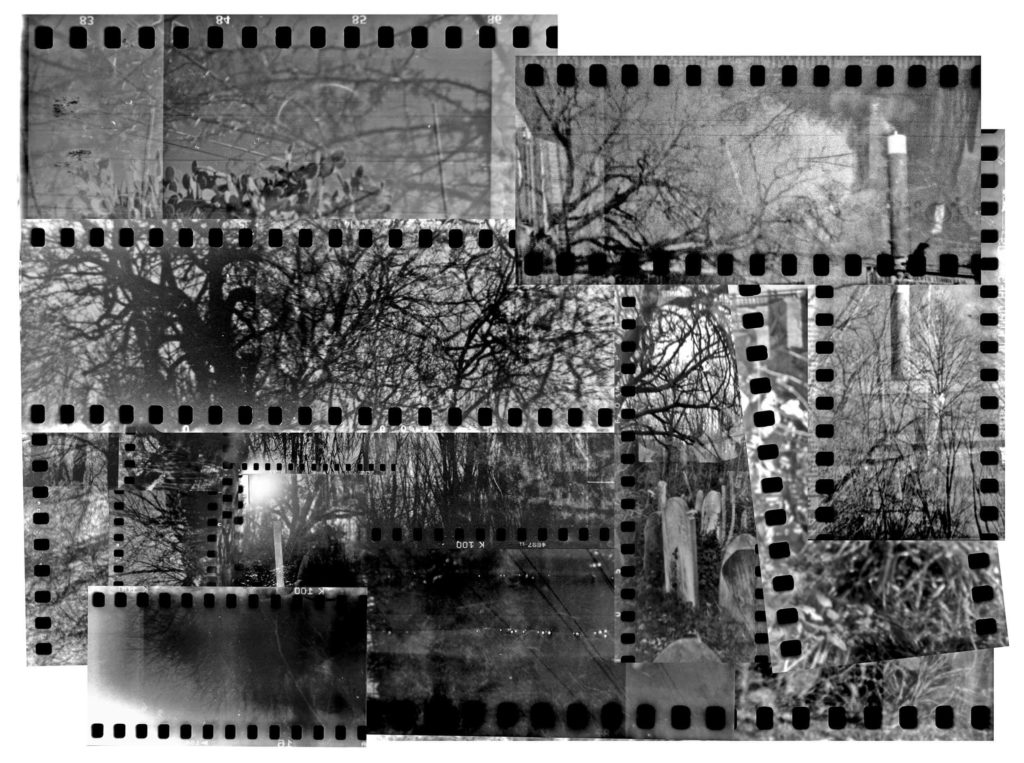

Dr Mary-Anne Potter of the University of the Witwaterstand describes trees as “straddling the line between being and becoming – being rooted and static, but also growing and diminishing.”

In her doctoral thesis Arboreal Thresholds – The Liminal Function of Trees in Twentieth-century Fantasy Narratives, Potter points out that trees “root themselves in a pre-industrial and pre-technological past”.

I’m interested in the mysticism that we imbue trees with, and analogue photography helps to emphasise this with the abstract and ambiguous images that arise from experimental darkroom techniques.

In a liminal space the elements of nature and machine or machine-made objects in these scenes co-exist amongst – or perhaps in spite of – each other, neither overwhelming the other one entirely.

But the difference is one of lifespan versus life cycle. A single tree might not outlast an ideology of a government, a religion, an economic model, or a dependence on technology, but its offspring can. With its ability to reproduce, a tree can replicate future versions of itself in the way that corporations, faiths, and political powers cannot.

Our fascination with ruins is archetypal: our primitive ancestors buried their dead 300,000 years ago. Whether it’s in Chernobyl or the Acropolis, humans have an innate fascination with the entropy of erstwhile empires. Perhaps it’s a similar perspective that staring at the stars brings: confronted with of the enormity of the universe and the inevitable endings of the our ideas, our creations, and ourselves.

“My name is Ozymandias, king of kings: Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!” declares Ramses II in Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem, Ozymandias.

The next line – written from Shelley’s contemporary perspective – reads: “Nothing beside remains”.

It’s this memento mori within the rubbles of ruins that reminds us of our dust-ward trajectory. But the idea of an endpoint at the extremity of this arc is something I want to challenge in my work through showing the presence of nature that our artefacts share a space with.

Eventually, one of these forces – artificial or natural – surpasses the other, and the threshold of liminal space is crossed. Above is a photograph of a girl in Kampot, Cambodia picking lotus flowers.

This scene speaks of a human venturing into a natural realm with a vast field of lilies, shuffling in the knee-deep waters of a floodplain.

However, the lotuses are growing on the remains of what is sardonically referred to as an “American pond”.

Almost three million tonnes of bombs were dropped on neutral Cambodia from 1964 to 1973, leaving the countryside peppered with eerie perfectly circular craters.

Eventually water trickled into this particular man-made depression. Lotus lilies found their way inside it, blooming and dying, but not before multiplying.

For several years, that American pond would have looked the picture of liminal space: two forces hovering in limbo – the colluding chlorophyll and the gash marks of the military-industrial-sized divot.

In this photograph, the organic overthrew the man-made: crossing the threshold and returning the space back to nature – the floating field of lotuses looking decidedly pre-industrial, except for their uncanny circular appearance of the body of water that they bob in.

While developing these negatives in the darkroom and arranging these landscapes, the question that arose was: If we – with our preoccupation with production and obsession with convenience – are sharing a liminal space with nature, which one becomes the afterthought when that threshold is crossed?