What used to be (Viivikonna)

DOI: 10.60650/EMPTINESS-E8CF-1682

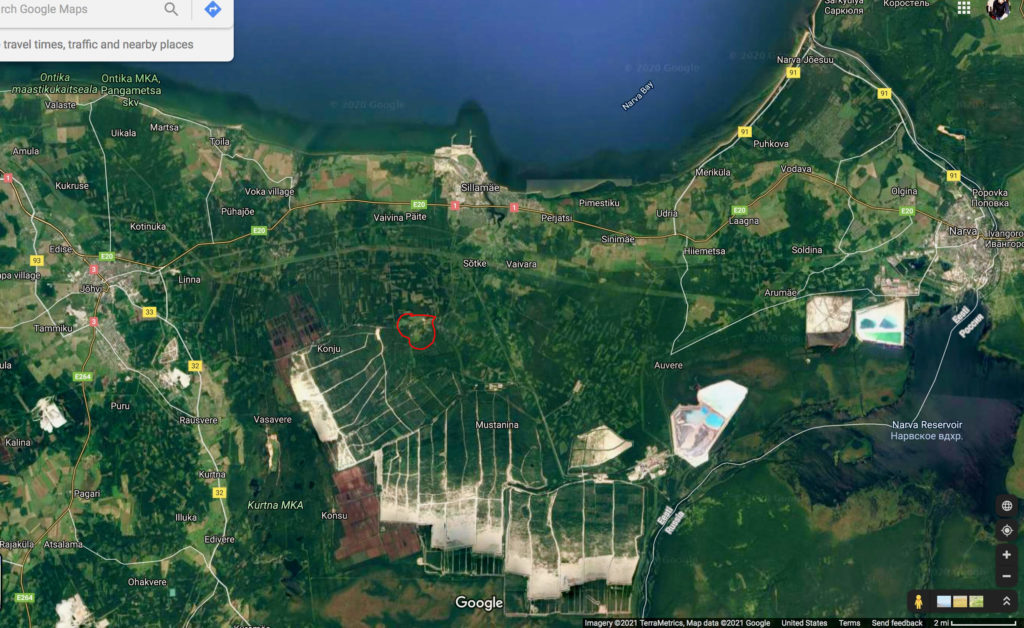

Once, Viivikonna was a ‘central’ mining town in Estonia; today, it is a remote village full of emptiness. Walking around the place, you can still hear the metallic sound of a train (of modernity?) just beyond a hill: so close and simultaneously so far, as it does not stop here anymore. The train connects a new point of extraction with an old area for processing and distributing, leaving behind sacrificed, non-inhabitable landscapes.

The first settlements here were established in 1935, next to an oil shale mine. They were started by the interwar Estonian Republic (1920-39), and under the Soviet Regime the settlement became a town. Its growth was linked to producing 200,000 tonnes of oil shale annually for use all across the Soviet Union. The town grew rapidly and was populated by people arriving from every corner of the USSR. In the 1950s, Viivikonna already had a population of 1,800 inhabitants. Most of its architecture, or the now strange materialities that used to be buildings, is Stalinist. Solid, monumental housing for an intrinsically temporary and exhausting project. As the quarry and mining moved further to find new territories for exploitation, the town of Sirgala had to be created, this time with Khrushchyovkas, low-cost, concrete-panelled apartment buildings that were developed in the USSR during the 1960s.

The downfall of Viivikonna started in 1974, once the mine dried up and people started to move away. It happened slowly in the beginning, and sped up after the Soviet Union broke up. Originally, the decay of the town had to do with the exhaustion of resources rather than the collapse of socialism. Then, the collapse of socialism exacerbated the decay, for there was no Soviet system that could keep up the towns and settlements that had lost their initial purpose.

In the last few decades, the population has decreased from 2,200 to barely 50 inhabitants. As a number, 50 does not say much. As a community of neighbours, each of them is deemed very important to keep the settlement inhabited. Indeed, as you walk around, you do find different signs of human life. A dog moving restlessly, the imprints of human steps in the snow, the floating sounds of a radio (like an ancestral echo).

During my first visits to Viivikonna, post-apocalyptic images came to my mind such as the Zone from Stalker (a 1979 film by A Tarkovsky), with the wilderness after civilization and decaying infrastructures standing as evidence of modern devolution; I was also reminded of Agdam, a town of nearly 40,000 inhabitants, that was totally destroyed in the first war of Nagorno Karabakh (which I visited in 2015). I believe one could feel the same around Pripyat, abandoned but not vanished.

These are landscapes of ‘no more’, sacrificed (Martínez and Agu 2021), removed from the possibility of a future, yet with many things still going on there. They might be almost empty of inhabitation, but not of relations and problems. We encounter these landscapes of displacement as residual and excessive, with trees growing inside former houses, now carcasses – filled with solitude, fear, and the melancholia of non-creative destruction.

In Viivikonna, however, history has no record of war, plague, or nuclear explosion. The urbanity of the settlement simply vanished, as quickly as it had come. Viivikonna’s emptiness comes into view because its past fullness is not gone, but rather retreated (Dzenovska 2020). And yet, with repeated visits, this town becomes less exotic and frightening; one could even imagine living there.

“These days, nobody uses this road much,” says a local. Some roads are almost gone, vegetation has taken over the pavement. Remoteness is felt in used-to-be paths and roads, in liminal mistrust and what endures against the grain. In Viivikonna, cars appear as signs of civilisation and inhabitation. When there are no cars around a building, it means no one lives there. No footprints around it means no one has walked there today, or this week. Still you walk on the main street, Rahu (peace), and suddenly find an orange mailbox on the façade of the former post office.

Some modern infrastructures still work, even if precariously. Water, electricity, and heating systems work. Communism was, first of all, Soviet power plus electrification. Nevertheless, the village is poorly connected with public transport. Only bus no. 33 runs between Sillamäe and Viivikonna four times a day. As there is no grocery store, some of the neighbours who don’t have cars (many of them elderly) take the bus to Sillamäe (11km away)[1]Sillamäe is a former atomic town that has also been losing population: 20,104 inhabitants in 1994; 12,480 inhabitants in 2020. and come back by taxi, at a cost of 7 Euros.

Viivikonna has become popular among bohemian strangers wanting to contemplate the broken dreams of modernity and the spectacle of decay (DeSilvey 2017). For decades, the only visitors were thieves coming to remove valuable construction materials such as metal from the existing houses. However, in the last few years we have seen an increasing number of voyeurs following dark tourism postulates (some websites labelled Viivikonna as a ‘cool place’ and an ‘Off-the-beaten-track ghost town’).

People from Kohtla-Järve (other former mining area of Eastern Estonia) refer to Viivikonna with sorrow and apprehension, as an example of des-urbanisation that could come to them if they do not take preventative measures (in a new take on horror vacui, or fear of the empty space). There are those who even say that the place is cursed. Around World War II there were several concentration camps in the area, built by both the Nazi army (with Jews sent from Vilnius and forced to work in the mines) and by the Soviet army (with German POWs made to build the settlements and work in the mines).

You keep walking, however, and encounter mundane signs of life. You find small gardens, vegetable fields, a green house, a snowman, a self-made heating system behind semi-inhabited houses…they are all affirmative forms of world‐making. Not long ago, Liina Hallik, journalist of the newspaper Õhtuleht, published an article talking to a family who decided to move in when everybody was leaving. Liina starts with these words:

“I arrived in Viivikonna with certain prejudices. A ghost town. A former mining town. Extinct. Broken. Terrifying. Empty streets loom before my eyes, and crows are ominously creaking at the top of wooden clogs. It is as if dark blue clouds are floating in the sky to confirm the foreknowledge. Driving into the infamous ghost town, we are greeted by cheerful wooden figurines and a romantic well with a cake in the middle of a carefully mowed lawn.”

Then she tells the story of Valentina and Nikolai, who moved to Viivikonna 24 years ago: “When normal people started moving out of the town, we came here. We left the apartment in Sillamäe to my daughter. She got married and children were born”. Years later, their daughter also moved to Viivikonna, buying the house next to her parents (real estate is cheap and plentiful in the village because most don’t want to live there). However, most of the inhabitants stay because they don’t have anything better, as Dasha – a local neighbour – explains: “Originally, we didn’t have money to buy an apartment somewhere else, so we stayed. Then, you get used to the idea, and carry on living”.

Here, not only does real estate have little value, moving to Viivikonna is seen by some like a punishment or forced retreat. Elena, a neighbour in Sillamäe, has just such an opinion. She says that the town of Viivikonna is for those who barely work, for pensioners and drunkards: “When someone is not able to pay for rent and utilities here, then they are sent to Viivikonna”. But what kind of debts? “Heating, rent, utilities…”. And how do they make a living there? “I don’t know, still they find money to buy alcohol”.

The former school, now in ruins, is one of the most symbolically charged buildings. On my first visit, I saw a few children hanging around the bus stop. They go to the school in Sinimäe (9 km away).[2]Sinimäe has over 300 inhabitants and it’s known because of an important battle in WWII, The Tannenberg. Basic services like this have been closed down since. Ambulances come from Sillamäe to Viivikonna, but only in the case of an emergency. In the neighbouring village of Sirgala the situation is even worse, as there are people who live in apartment buildings without electricity, central heating, water, and sewerage.[3]Sirgala is just 4km away and shares the same history, yet the material conditions are worse than in Viivikonna and around 20 people live there.

It is hard to imagine social reproduction happening in certain contexts. In these times of pandemic and confinement, remoteness might be an advantage, though. You can grow vegetables in your little garden and tinker around without worrying about keeping physical distance. Local people do not need to wear a mask; there is little contact with the outside world and its affairs, with history and politics.

Global flows only pass by Viivikonna: on a train with oil shale that does not stop here anymore. The optimism of modernity and of socialist visions of progress has long vanished in this town, leaving behind strange in-between materialities, neither belonging to the realm of the urban nor of the rural. Decay has its organising principles; yet the decay of these settlements has not been a post-mortem act of justice against the Soviet regime, but of neglect and political abandonment.

This blog is based on the article ‘Far away, so close: A collective ethnography around remoteness’, written with Eeva Berglund, Rachel Harkness, David Jeevendrampillai and Marjorie Murray and published in the journal Entanglements (2021). I want to thank my co-authors for their dialogic editing.

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the CC-BY (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International) licence, which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Sillamäe is a former atomic town that has also been losing population: 20,104 inhabitants in 1994; 12,480 inhabitants in 2020. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Sinimäe has over 300 inhabitants and it’s known because of an important battle in WWII, The Tannenberg. |

| ↑3 | Sirgala is just 4km away and shares the same history, yet the material conditions are worse than in Viivikonna and around 20 people live there. |