“War on the horizon”: fieldnotes on infrastructural vulnerability in frontline communities of the Donbas

DOI: 10.60650/EMPTINESS-XWHK-5C02

At 10am my overnight train from Kyiv arrives in Kostiantynivka – a relatively small industrial city of 70,000 inhabitants. Prior to 2014 it used to be just a brief stop en route from Kyiv to Donetsk, but now it is the last station served by this train, dubbed in popular discourse as ‘train Kyiv-war’. (There is even a documentary film with such a title, depicting the people travelling on the train, from military to IDPs and volunteers of humanitarian missions.) I was commissioned by an international NGO to conduct fieldwork in two frontline villages, and my driver is already waiting for me at the platform in a blue vest with the NGO logo. As we leave the city and head south towards Yasynuvata, we pass the first block post. “This one is just the police. There will be two more on this highway to Yasynuvata and Donetsk, military ones. Actually, there are three more, not two, but we can only pass two, the third one is off limits“. Almost immediately, I ask the driver to stop, overcome by the beauty of the surrounding landscapes. It turns out that we are passing through a nature reserve ‘Kleban-Byk’. “It took a while for this nature reserve to be cleared from landmines. Now it is safe again – look there at all the men fishing! And in the summer one can also swim here, or make a barbeque.“

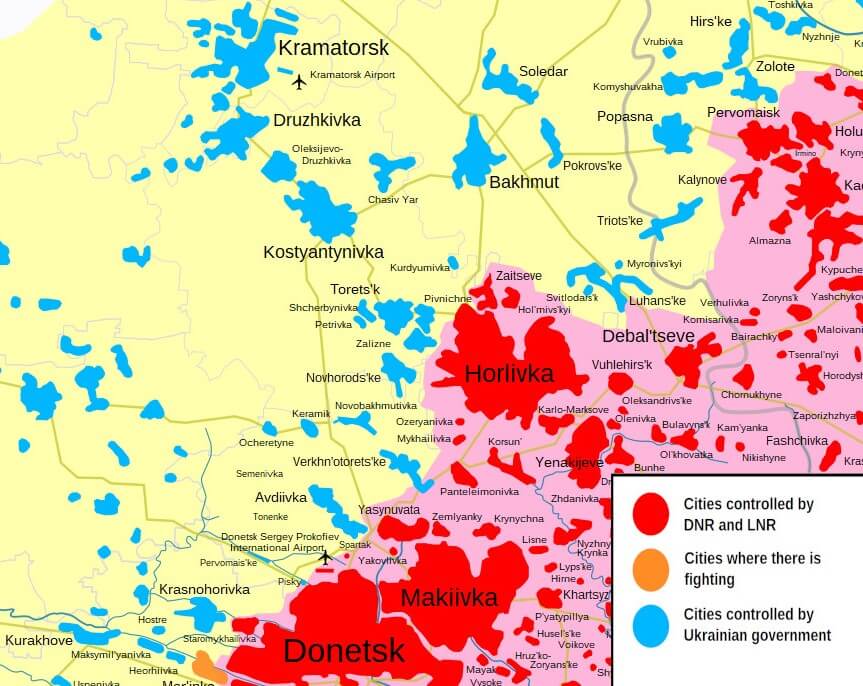

I take a few photos and observe that this is not the stereotypical image of the Donbas: “I didn’t expect to see such natural beauty. I thought it was just coal mines and heavy industry – but look at all these open spaces and wide blue sky!” The driver smiles: “Oh, but there were mines and industry too! Look, way there on the horizon, see those blаck hills? Those are spoil tips from the Horlivka mine. And this highway? Before you could have reached Donetsk in half an hour, there were so many cars, it was always busy“. He pauses and sighs, “Of course, all of it remains on the other side now, and we are cut off from everything“.

In this blog I explore the concept of horizons in the war zone. I look at how residents of frontline communities in Donetsk region engage with horizons that remain fixed on the demarcation line, constantly reminding them that their familiar geographic, economic and social networks are fractured, that now “all of it remains on the other side” and they are “cut off from everything”. I ground my account in the fieldwork I conducted in two villages in the former Yasynuvata district, at 5-10km from the frontline and at about 20km from Donetsk.

Growing up, I learned that horizons mark for us the limits of what we can see, but not the limits of the world. I learned that as we move forward the horizon moves with us, and things that seemed distanced are now easier to grasp. I learned that it is possible to ‘broaden horizons’ and to look at the horizon as an invitation to explore and to engage. The very concept of horizons was politically laden, intriguing and optimistic, even utopian. But as I stare at the spoil tips from the Horlivka mine, that notion is all of a sudden shattered. In this land, horizons are sad and heavy; they mark losses, not possibilities; and they close space down instead of opening it up.

The village dwellers who come out to greet me give me a little tour and point also towards the horizon. The spoil tips from Horlivka coal mine are even closer now, at less than 15km to the east. “Many of our men used to commute to work there. But the mine was blown up, flooded, and anyway it is now on the other side.” At the other end, 15km southwest, they point to the smoke from the Adviyivka coke-chemical plant. It is walking distance from Donetsk airport which was renovated for UEFA Euro2012 but completely destroyed in 2014. The little forest just outside the village was a favourite hunting, picnic and barbeque spot, but hunting is now banned (as shooting could be confused for violation of ceasefire), and “anyway there could be landmines there”. The railway crossing is blocked and if we were to walk a bit further, we would see a destroyed railway bridge.

I am shocked to see how nearby everything is, and yet, inaccessible. At first glance, it’s just an ordinary Ukrainian village, but all my informants alluded to the formerly vibrant production networks into which they had been inserted. Donetsk was the fifth largest city in Ukraine according to the 2001 census, with a population of about one million. But if we consider Donetsk metropolitan area, it was likely to come second after Kyiv, with more than two million inhabitants. Numerous smaller cities and even villages like the ones I was visiting formed an industrial network, centred on coal mining and heavy industry. Donbas was responsible for 16% of GDP and 25% of Ukrainian exports, so war had significant consequences not just for the region, but for all of Ukraine. Economic decline was related to physical damage and destruction of industry, highways and railway networks, and the inability to access these industrial sites from the Ukrainian side due to new internal ‘borders’ emerging. The coke-chemical plant in Avdiyivka is the only industrial enterprise in the vicinity of the villages that remains on the Ukrainian side – but now that coal supplies have become more limited with many of the mines remaining in separatist-controlled regions, the plant also cannot produce at its full capacity.

Residents of smaller towns and villages commuted to Donetsk and neighbouring cities not only for work but also for access to most social infrastructure, such as hospitals, centres for administrative services, institutions of higher education, etc. Moreover, many urban residents had relatives and summer houses in nearby rural communities, while elderly village dwellers kept in touch with their children in cities, looked after grandchildren during summer vacations, and passed on sacks of potatoes and canned vegetables. These networks were abruptly cut off in 2014. Frontline communities some 10-20km from Donetsk became isolated economically, geographically and socially.

The sense of being geographically ‘cut off’ and infrastructurally vulnerable is aggravated by ongoing administrative changes. As bigger cities remained on the other side, the Ukrainian government attempted to reconfigure borders for new administrative units. In my case study, the two villages were forcibly attached to Ocheretyne (a town with only 4,000 residents [10 times fewer than Yasynuvata] and little administrative experience). The village dwellers are still confused about who is responsible for what, and where to turn to if they have any needs or questions. For example, water and electricity are provided to the general public from Adviyivka, but the centre for administrative services was moved to Ocheretyne (although many village dwellers were unaware of its existence). The hospital in Avdiyivka seems to be closer, but for some reason patients are sent to Kostiantynivka, which is further away. A person may have to travel to three or four different cities for one administrative or social service question.

As I enter the local clinic that employs just one nurse and offers consultations by a visiting family doctor once a week, I notice how cold it is inside, even on a sunny April day of more than 20 degrees Celcius outside: “If it’s so cold now, what happens in winter?” – “We ask our patients to let us know ahead of time if they are planning to come, especially with infants and young children. That way, if we know they will come, we have enough time to find some coal and warm up the room.” There is one ambulance in the newly created district centre of Ocheretyne, but the local hospital is too small and lacks doctors so patients often need to go to Kostiantynivka anyway. The local ambulance stops at a block post and waits for the next ambulance from the city to pick up the patient and bring them to the hospital. “We sometimes wait for a whole hour for the ambulance to reach us – it’s a better idea to just hire a car and go to the hospital on our own, but it costs 600 hryvnias [£15], and not everyone has that money, given that a monthly pension is 2000 hryvnias [£50].” Even if they find a car, people often don’t know where to go and whom to contact. “Formerly our family doctor knew all the specialists in Donetsk, Horlivka, and Yasynuvata. She could refer us to this or that hospital, knowing that they have the best doctors. But now she says, ‘I don’t know who to refer you to, all the doctors either remain on the other side, or moved to Kharkiv, Dnipro or Kyiv…’.”

This fractured healthcare system is a vivid example of how the socio-economic context in frontline communities is marked by disruption of previously existing networks. These include transport networks (both for personal commuting to work and for family reasons, and transport to ensure economic activity), economic networks (jobs that “remain in occupied territories”, jobs lost due to destruction of industrial objects), infrastructural networks (administrative and social services, in particular healthcare), and social networks with family and friends. Such networks gave people a sense of order and security, a feeling that “everything works as a mechanism” and they know their algorithms of action in different life situations.

The central square of the village (if it might be called a square), which was recently repaired at the village dwellers’ initiative, sums up their longings for safe communal spaces where they can engage socially and politically. A playground, where children can play, turned out to be one of the top priorities for local women – to the surprise of donors who were thinking of more urgent needs. “We need a space where we can sit and chat, while our children are playing safely, because otherwise we are stuck at home all day….” An amphitheatre with rows of benches was also greatly appreciated by village dwellers – a space where they can meet for concerts by the schoolchildren and local women’s choir, hold meetings with their council representative, and have church gatherings. Next to the playground and the amphitheatre is a monument to a Soviet soldier with the words “nobody is forgotten, nothing is forgotten”, which village dwellers point to when speaking about the ongoing war.

All village dwellers whom I talked to insisted that what made their village ‘alive’ was this square, along with the school and the clinic. So while decentralization reform suggests that such infrastructural objects should be ‘optimized’ and unified into a bigger school or clinic in the central and largest village in the district, my informants insist that economic efficiency is not the only question at stake. The struggle to keep the school, the clinic and the square are both political demands as well as preconditions for political participation. Infrastructure is not just a list of basic needs that vulnerable groups in frontline communities have (as both governmental and NGO reports often present them) but spaces where people can engage with the world in meaningful ways as social and political agents. Thus, the destruction of previously existing networks is much more than a list of industrial and infrastructural objects that remain destroyed or inaccessible due to war. It is about infrastructural vulnerability that leads to a sense of fragmentation, of narrowing down of both spatial and temporal horizons. There is no point in looking that far on the horizon towards Donetsk, because one can no longer get there. There is no point in planning strategically for the long term because it would require a kind of investment in a fragile and uncertain terrain that neither the state, the NGOs, nor the individuals are willing or able to make. As Wladimir Sgibnev and Lela Rekhviashvili note in their 2021 article on post-Soviet infrastructures One modernity lost, the other out of reach – Contested post-Soviet infrastructures:

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, severe funding cuts, mismanaged privatization, inadequate maintenance, and widespread depopulation resulted in extensive failures in transport, water, heating, electricity, or healthcare provision. The dismantling of the Soviet Union marked the disruption of infrastructures built on the assumption of political – and thus technological – unity…. Regional conflicts resulted in borders cutting through elaborate railway, pipeline, or electricity grids. Yet, perhaps most significantly, the shift from a centralized infrastructural regime to individualized, fragmented, and ailing systems affected the relation between citizens and the state.

The relation between citizens and the state can now be summed up as ‘patching up holes’. These are specific small-scale efforts that are manageable (and where NGO assistance can be obtained), where the state can ‘tick the box’ and write a report to show that at least something was fixed, e.g. five new water wells were installed. Of course, this is not enough: water disappears in the hot summer months, the harvests suffer, and the Ministry of Emergency Situations has to bring in drinking water to vulnerable groups (along with private providers at one hryvnia per litre for those who do not qualify as vulnerable). But five new wells are better than nothing, at least we can report on some improvements.

The entrance to the rural council is now wheelchair accessible. Who will go to check whether the two elderly men on wheelchairs, who live several kilometres from the rural council, have ever used it? There is no public transport, let alone special wheelchair-accessible transport or straight paved roads on which one could move around the village on a wheelchair. But the council fulfilled the new accessibility requirements sent from Kyiv.

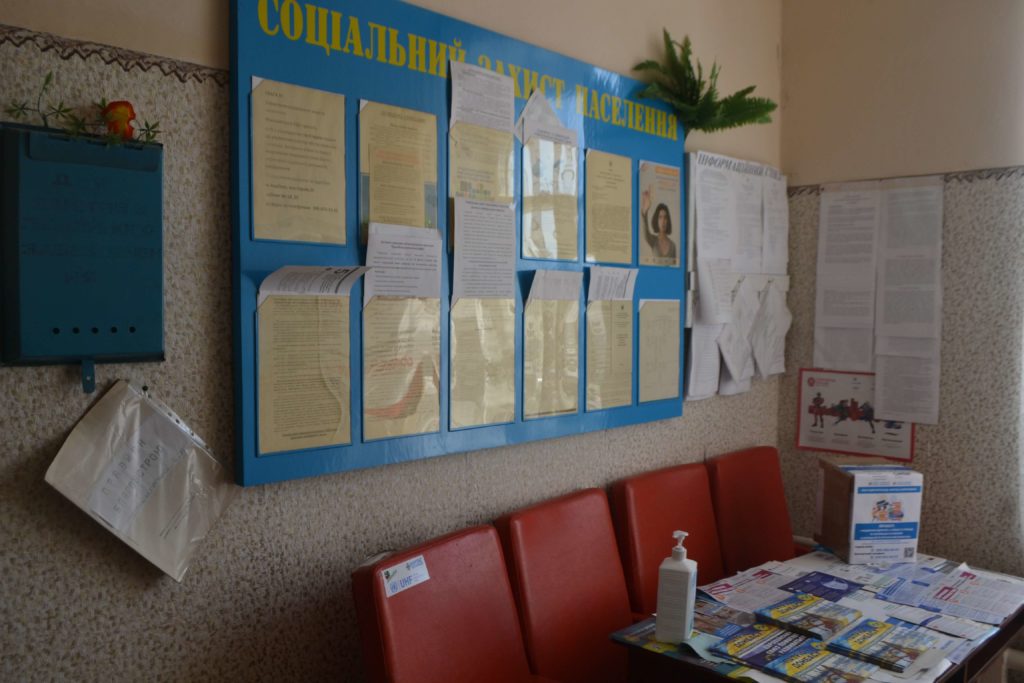

Some leaflets about domestic violence prevention lie on the table at the entrance of the rural council building. Is there a policeman responsible for handling domestic violence cases in the village? Where is the nearest shelter for victims? Do people believe it is indeed possible to “break the cycle” as the leaflet says? But there was an information campaign, leaflets were handed out, photographs taken.

Humanitarian efforts are just as fragmented and haphazard, with long lists of vulnerable groups. Who will qualify for aid this time? “Why do the elderly get everything? They can soon open shops in their houses, selling canned food and hygiene items!” “Oh, but single mothers never leave with empty hands! It looks like it’s better to hide your husband and pretend you don’t have one!” “Why do they set this stupid rule that you must be over 60? I’m also handicapped, so what that I’m 57? How am I less in need than them?” Success is measured by reports on targeted assistance – library windows, shattered by bombing, are finally replaced; the leaking roof in the kindergarten is repaired; social workers received a new bike to deliver groceries for the homebound, single elderly; a mobile doctor’s visit is organized to take blood tests and do ultrasounds.

I reach out for my voice-recorder and ask the first research question on behalf of the humanitarian NGO who sent me here: “What are the most urgent needs that you have in your community?” But I am embarrassed to ask it, because it narrows down even further the horizons of the possible. It’s narrowing everything down spatially to ‘your community’ – a small and homogenous space that people can understand and be part of (unlike the hostile bigger world). And it’s narrowing everything down temporarily to the ‘most urgent’ – something that we can quickly try to fix right away, so that everything doesn’t fall apart. But don’t ask for jobs, don’t ask for public transport, don’t ask for your familiar networks to be rebuilt, don’t ask for a broader political vision…. It’s all beyond the scope of our project, so think small, think what’s manageable, think of our limited resources, think about war on the horizon…

This blog translated into Ukranian was published in Commons: Journal of Social Criticism on 29 June 2021. The Ukrainian version can also be found here on the Emptiness project website.

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the CC-BY (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International) licence, which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.