The unmaking of Blackpool

DOI: 10.60650/EMPTINESS-Q0MZ-DN27

Someone arriving in Blackpool[1]Research in Blackpool was conducted in order to understand the broader migration patterns in the country of destination for those leaving eastern Latvia. on a Sunday evening a few weeks before Easter might find it rather sad. The lit-up promenade is empty (Figs 1 and 2). The backstreets – the streets away from the beach-front promenade – feature colourful hotels, some functioning, some closed for off-season, and others closed for good (Figs 7 and 8). There are mobility scooters parked by some of them (Figs 5 and 6). Their owners must be resting. The only sign of life is the amusement arcade identifiable by the cacophony of game-machine tunes (Figs 3 and 4). Inside it are families with children who have come to Blackpool for Mothering Sunday.

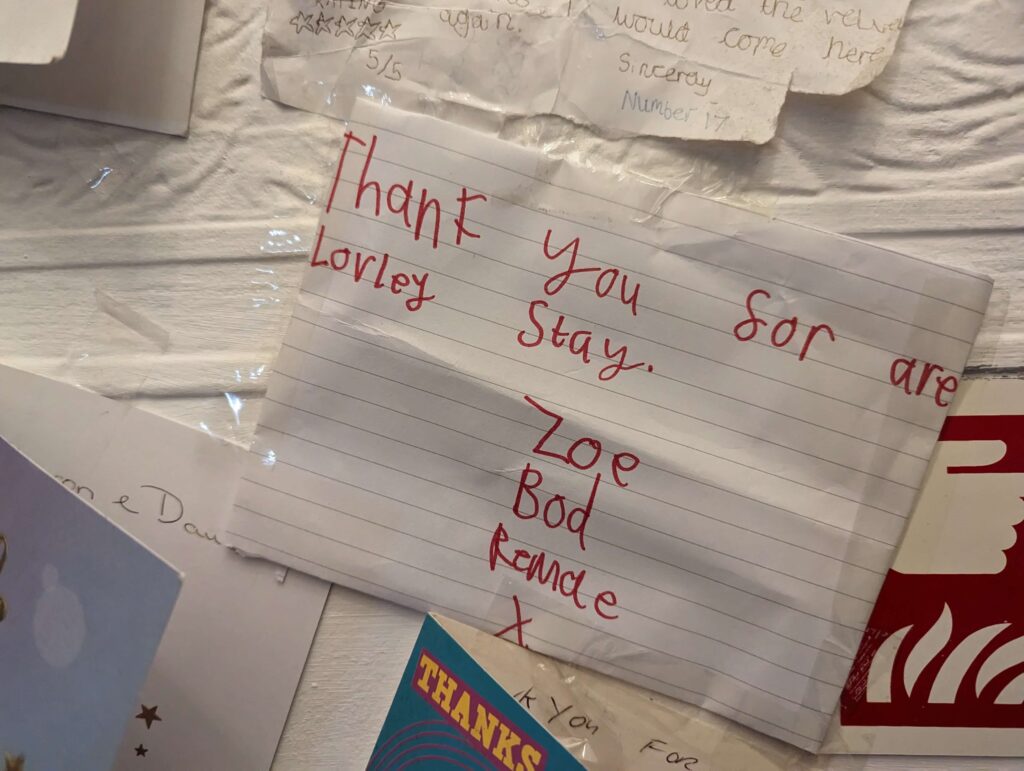

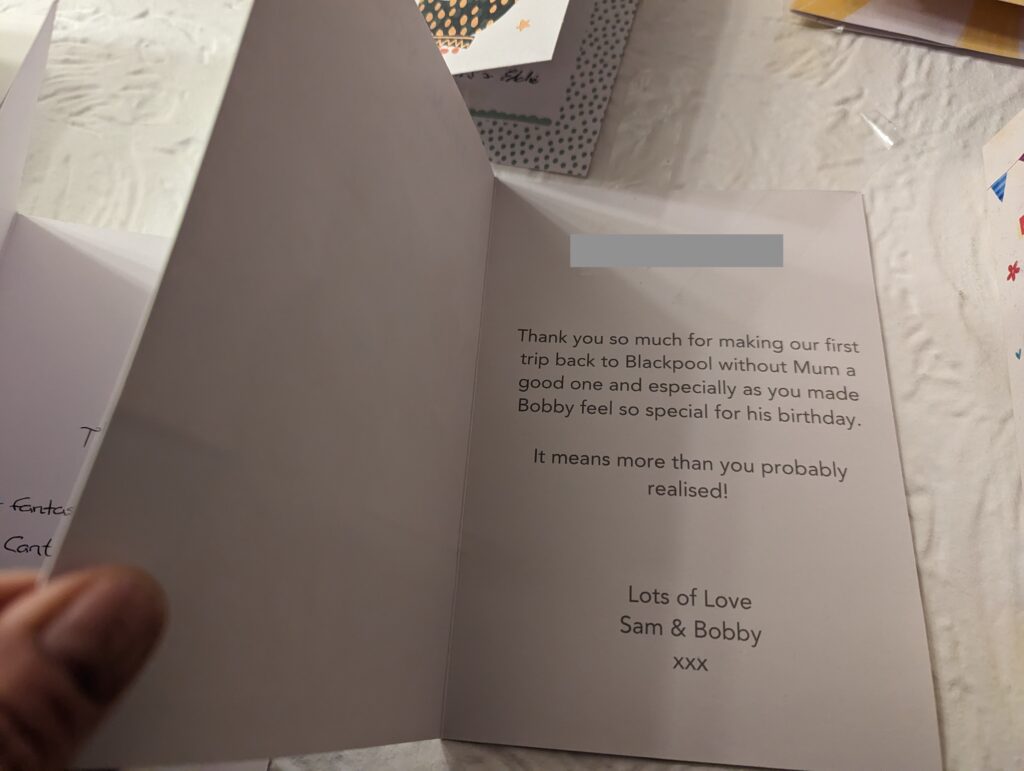

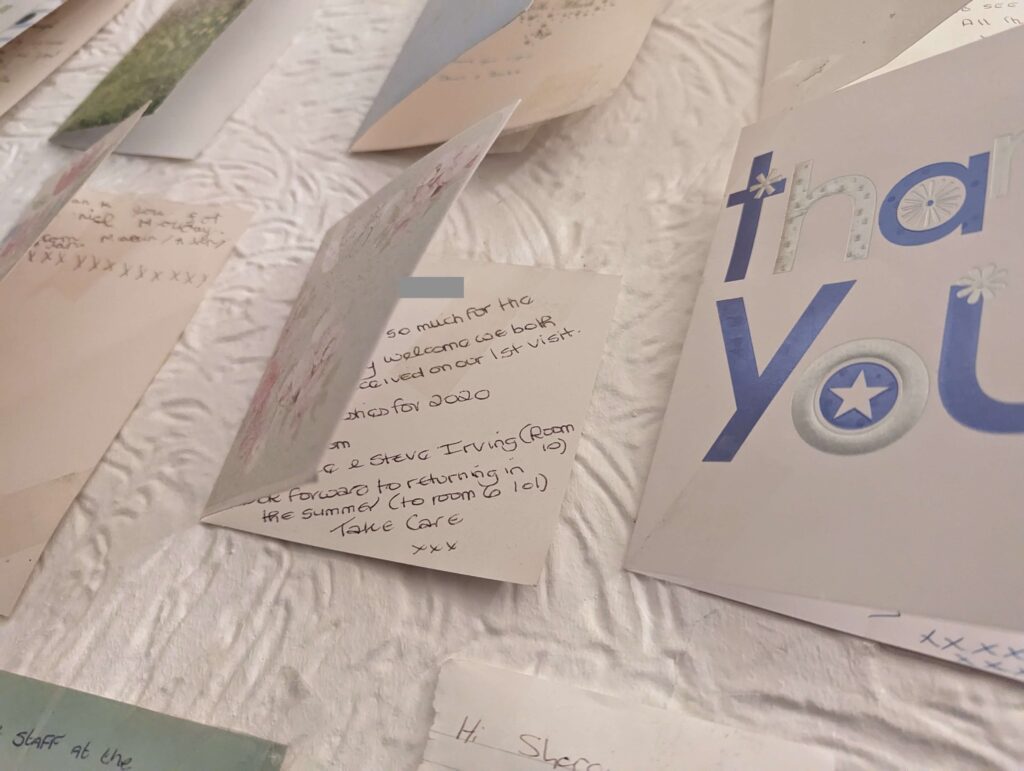

I ring the doorbell of my hotel, the last one in a row of terraced hotels, and after a while a man emerges. He is just below retirement age, has a gaping hole where upper front teeth should be, and is wearing a dirty white t-shirt showing off his tattooed arms. He doesn’t fit my image of a hotel host (I didn’t know I had one until I saw him). He leads me into a reception area decorated with plastic flowers (Fig 9). He is very kind, tells me he’ll make me breakfast at 9am, and I begin to believe that perhaps this is a proper hotel. The ‘thank you’ cards posted on the wall in the hallway provide additional assurances (Figs 10-12). Dan and Shelly[3]Pseudonyms used throughout. are being thanked for making a first holiday without mum special, for not changing the sheets every five minutes, and for the perfect breakfast toast. People promise to come again next year and wish Dan and Shelly all the best for the holidays.

When I meet Shelly the next morning, she looks just like the owner of the Blackpool Shawries Hotel featured on Channel 4’s Four in a Bed. She is committed to cleanliness, to her family-run business (they only have their son to help them, though her brother, a carpenter, comes to fix things), and to her guests. She remembers their faces, and Dan remembers their names. She has seen a generation of dancers grow up (Blackpool hosts an annual dance competition), who started coming when they were five and now some are taller than she is. “There aren’t many like us left,” she says. She means there aren’t many hotels left that can carry on the ways of the famous Blackpool landladies, whose image was fierce but who took care of their guests and had them returning year after year.

She is right. Empty store fronts, boarded up hotels, and crumbling buildings surround some of the still-functioning pubs, tattoo parlours, and fish-and-chip shops (Figs 13-17). Quite a few people in the streets are either drunk or on drugs. There are some kids running around, and some people look like they have somewhere to go. A weathered man with long white hair is standing in front of an open door (Fig 18). His dog runs back and forth in front of the house, stopping by the neighbour’s car and peeing on it repeatedly. The man has lived in this house for 20 years. What’s happened to all the hotels and establishments? “COVID,” he says. The scope of decay, however, seems much grander. The brightly coloured buildings amidst the boarded-up hotels deepen my sense of haunting sadness (Figs 19 and 20).

But this is not only an outsider’s view. Today’s Blackpool also appears sad to those who know it for much longer than I do. John of JJ Properties, featured in another TV show, in an episode of Nightmare Tenants, Slum Landlords on Channel 5, asks if I want to hear what Blackpool is like in layman’s terms. Having received a positive answer, he announces cheerfully: “It’s an absolute shithole!” “Do you want a brew?” he adds in a more prosaic tone.

John’s real estate firm specializes in finding housing for people on housing benefits who are ‘exported’ to Blackpool by southern municipalities, especially London boroughs, unable or unwilling to deal with the housing needs of their increasingly impoverished population (on the housing crisis and the unmaking of the British working class, see here). They are aided by companies, such as Reloc8, who take the surplus population off their hands and move them elsewhere. Blackpool is one such elsewhere. “They made such a good brochure about Blackpool,” says Karen at the Blackpool City Council, “that we couldn’t compete with it if we wanted to. They sold Blackpool as a fantastic place with fresh air, good education, and plenty of housing opportunities.”

The promised good housing is usually a former hotel converted into an HMO (‘house in multiple occupation’), owned by an absentee landlord and managed by a real estate company. The real estate company guarantees a constant stream of tenants on benefits. The landlord does not have to worry about finding tenants or caring for the property. In 2008, 38% of such properties were classed as ‘non-decent’, and things have only gotten worse. The Council is currently fighting to tighten regulations, while also trying to buy back buildings and make them suitable for living (the Council runs three real estate companies: one for social housing, one as a socially responsible landlord, and one as a private landlord that “needs to wash its face”).

“We import ill health and poverty, and we export brains and good health,” says a public health worker at the Council. “These people do not develop their alcohol and drug problems here. They come with them. We patch them up, and some of them move on, but many stay and go down a spiral. We don’t want to entirely get rid of the vulnerable population, but we want to find some balance. We cannot but be concerned with our borders.”

Some of those who belong to the ‘vulnerable population’ are settled in Blackpool because they are offenders or have just come out of a care arrangement, but many come on their own. Those who come on their own return to a place where they spent the happy days of their working-class childhood. This is what brought John of JJ Properties to Blackpool 32 years ago. He was a coalminer in Nottingham. When the mines shut, he “had a talk with his wife” and they decided to move to Blackpool and buy a hotel. They had been to Blackpool on their honeymoon, and they knew the town had a longer season than other seaside resorts because it had the Blackpool Illuminations in September and October.

The owner of the second-hand bookshop in the town centre came to Blackpool eight years ago, when he retired. He is from Yorkshire. He and his wife had been to Blackpool on their honeymoon. His wife had never seen anything quite like Blackpool before. They sought the Blackpool of their youth in their retirement.

Ellen, now 87, came to Blackpool in 1945 when she was 10. After her father came back from the war, her parents decided to move from their little village in Derbyshire to Blackpool and start a boarding house. They, too, had been to Blackpool on their honeymoon. They’d loved it. When the family moved to Blackpool, Ellen thought she was in paradise. She thinks, though, that it must have been hard for her mother who took care of the boarding house while her father went to work. Later, Ellen got married and bought her own hotel. They went into partnership with another couple. Ellen’s husband did the cooking, and the other guy tended the bar. Ellen became a true Blackpool landlady. She traces the beginnings of her success to the arrival of four Glaswegian lads early on in her days as a hotel owner. They were drunk, missed their train, and somehow ended up on the street next to her hotel. She took them in and made them a plate full of sandwiches. They left the next day. After that, they kept coming back year after year. They brought their wives, their children, and then their grandchildren. “I built our business on a plate of sandwiches,” Ellen chuckles.

When Ellen and her husband ‘retired’, they sold their 22-room hotel and moved to a smaller one with five rooms. It was in the 1990s. In those days, many people from the south were coming up to Blackpool and buying hotels. Housing prices had skyrocketed in London, and Blackpool businesses were suffering from lack of generational continuity. Ellen was lucky that her son and daughter-in-law “went in with them” on the smaller hotel, but many people’s children went to university and never came back. “We got an awful lot of southerners back then,” Ellen shook her head:

You could buy a hotel here for £160,000. That’s how we sold our big hotel. We sold it to a nice couple. We thought they would take good care of our clients. They had owned a restaurant in London. But they messed it all up. We left them the hotel in September with a full booking for Christmas. We told our old clients to come around for Boxing Day to say hello. And they came on the morning of Boxing Day and told us that they could not take it anymore, they were leaving. We used to cook a whole turkey for Christmas, the hotel smelled nice, but this new couple had served sliced and warmed up turkey that didn’t smell like anything. Everyone was leaving. We felt bad, but what could we do?

John, the bookshop owner, and Rob – a man having his morning coffee by one of the remaining Blackpool hotels – came for the dream world made by people like Ellen. Now the dream is gone. One-third of the hotels have closed down and been remade into HMOs (you can tell by the numerous bells on the front door). The pubs have shut down.

“You know Basil Newby?” Rob asks. Basil was known as the ‘Emperor of Blackpool’. He painted the town pink (Basil would later tell me that Blackpool was, in fact, known as ‘Basilpool’). He rode a pink Rolls Royce and owned eight clubs. Now he only owns three. Rob himself owned a hotel in the North Shore area. But he sold it in the 1990s and went to Liverpool. He still comes to Blackpool to see the shows, especially Basil’s Funny Girls (Figs 21-24). But it’s not the same.

And yet, Rob still comes. How can you forget the parties, the comedians, the good times? Hylda Baker, the famous comedienne, once brought a monkey with her, Basil recalls. The monkey pooped all over his parents’ hotel and had to be thrown out. Those were the days! Theatres were “chock-a-block full”, you couldn’t get a seat!

The working class that saw Blackpool in its heyday is getting old and coming undone. That’s why there are so many mobility scooters around. The remaining hotel owners, many without skills and without the ability to run a working-class resort when the working class is disappearing, are doing what they can. They try to offer everything on site – you get your breakfast, go for a walk, come back, play bingo, and scoot to the Funny Girls club in the evening. Your kids no longer want to come with you, and they no longer want to run your hotels.

Nancy is among the few ‘sandgrownians’, people born on the sands of Blackpool, who has returned to take over her family business (Figs 25-27). She spent seven years in Costa Del Sol and came back in December because her grandmother died and her mother could not run the café anymore. In Spain, she worked in catering. She worked for a friend. As she pours me coffee, she tells me that today, just at this hour, her friend is being buried in Spain. She was only 42. She drank herself to death. When Nancy’s friend’s father, who was an alcoholic, died a year ago, her friend started drinking and never stopped; her brother also died from alcoholism. Nancy herself enjoyed her life in Spain. She worked for British businesses. There’re lots of Brits in Spain. There’re lots of drinking and drugs in Costa del Sol. There are people who run from the law in the UK and go to Spain.

The sun hasn’t come out since she’s been back. It’s been slow in the café as well, with only a few construction workers coming in from time to time (they stay in a hotel nearby because they have nowhere else to live). Someone has bought the crumbling building across the street, and there is renovation going on. Nancy hopes it will be done by the summer, but she doesn’t know whether the building will be a hotel or residential housing. She is trying to get her business going. Her food is good. She wants to make some improvements – put some lights up, put some tables in the parking lot.

Outside of Nancy’s café, the sinews of Blackpool are coming undone: family-owned hotels frequented by multiple generations of working-class families are disappearing. The British working class itself is disappearing into a mobile, flexible, and precarious middle class and a rapidly growing sub-proletariat that is flocking – or being ‘exported’ – to Blackpool.

The undoing of the British working class goes hand in hand with the undoing of community and family. Blackpool businesses were run by families, and they were visited by working-class families. There were generations of hotel owners and their guests. In today’s world, however, being tied to family and place – crucial constitutive elements of the working-class habitus – is seen as a handicap. Such ties have come to represent lack of physical – and thus social – mobility. Researchers note that Britain’s seaside resorts are among the most deprived areas of the country, yet some of its most impoverished population is immobile because it lacks skills and remains committed to the value of staying local passed down through generations. But it is precisely mobility that is further impoverishing the people being ‘exported’ from London. Their family and community ties are broken, and their lives are far from the dreamlands of their seaside honeymoons. But then, even in its heyday, “Blackpool was like marmite,” says Basil. “You loved it or hated it.”

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the CC-BY (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International) licence, which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.