Saving Teriberka: how urbanites are remaking a ‘depressed’ region

DOI: 10.60650/EMPTINESS-VNCT-ND83

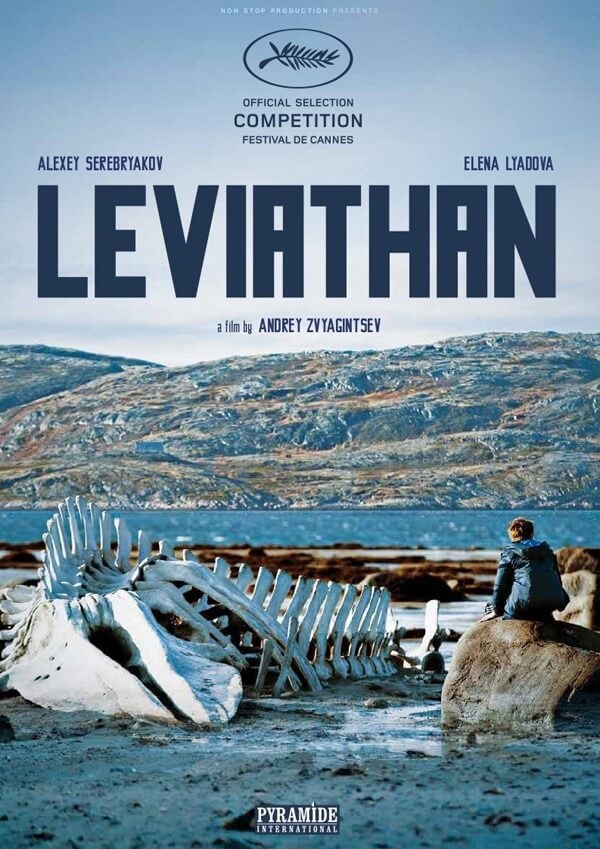

The Russian economic-geographical classification system includes a category ‘depressed’. It is used to designate regions suffering from persistent economic downfall, frequently caused by industrial crises, as well as from a range of negative social and demographic trends, such as mounting unemployment, massive out-migration, degradation of infrastructures, and considerable decline in the quality of social services. Lacking the domestic resources to overcome these types of crisis, such localities usually depend on financial support from the regional administration or, most typically, the federal government. The category is also commonly used in the Russian news media, internet, and television broadcasting. As popular and widespread as the label ‘depressed’ is, a number of related markers are also used interchangeably to describe such localities. For example, a ‘depressed backwater’ (депрессивная глубинка) could be portrayed as a ‘ghost city’ (город-призрак), ‘the lost world on the edge of Russia’ (затерянный мир на краю России), a ‘godforsaken’ (богомзабытый) area (settlement) struggling through a gloomy present and awaiting an apocalyptic future. Besides the social anxieties that these descriptions regularly provoke, they also contain dramatic potential, which is being grasped and elaborated upon by photographers, filmmakers, sound and visual artists. It was this imaginary of a vulnerable and dying-out rural Russia, powerless or abandoned by the state, that shaped the plot of one of the most popular Russian non-mainstream films of the 2010s – Leviathan by Andrei Zvyagintsev (2014).

Leviathan tells the story of a village man who tries to protect his family and home from a corrupt local bureaucrat – an embodiment of the cold-blooded and oppressive state. The bureaucrat eventually takes hold of the family’s land, demolishes their house and builds a church in its place. The majority of outdoor scenes were filmed in a small settlement of Teriberka located on the shore of the Barents Sea. A seasonal fishing camp during the time of the Russian empire, during the Soviet era Teriberka became a permanent settlement comprising several collective farms and a prominent ship-repairing facility. The decades of post-Soviet socio-economic transformations, however, caused the shutdown of all major enterprises in the village, considerable population decrease (from approx. 2,400 people in 1989 to 851 in 2017), and gradual decay of all vital infrastructural systems. The ruins of industrial sites, the rotting carcasses of wooden ships, and the run-down houses made Teriberka a perfect setting for the social conflict between an individual and the state that unfolded in Leviathan. Despite the film’s fictional nature, for a small segment of the national audience Teriberka became ‘a symbol of all Russian misfortunes’ (символ всех российских бед), a cluster of social problems that the state had failed to solve. At that time (2014-15) these people – the majority of them living in Moscow – had never seen the actual Teriberka; so their only sources of information about it, apart from the film Leviathan itself, were regional online publications reproducing the depression discourse. Nevertheless, this group of outsiders decided to ‘save’ the village – to visit it, clean it, and breathe life into its emptying environment.

Contemporary studies of rural areas draw critical attention to the analytical capacity of a rural-urban dichotomy that produces, maintains, and reestablishes hierarchy, where the urban stands for ‘urban modernity’ and progress while the rural connotes backwardness. This specific mode of imagining rural sociality as anti-modern, both spatially and temporally distant (remote and backward), is typical of political, academic, and popular discourses in Western modernity, including in Russia. It leads to marginalization of the rural ‘framework for human living’ – making rural areas the depressed space per se. One interesting effect of the perception of rural spaces as intrinsically backward is the emergence of all sorts of grassroots projects and fantasies about possible ways to revive and restore them. Such fantasies usually emerge among urbanites who take it upon themselves to bring dying villages back to life. This is what happened in Teriberka when a small association of well-to-do Moscow boutique farm stores and restaurant owners called ‘LavkaLavka’ decided to fight depression and emptiness using a range of well-known tools of neoliberal development, such as stimulation of tourism and establishing a local tourist attraction – a Teriberka festival.

One of the founders of LavkaLavka, Boris Akimov, looks back on the birth of the idea in a documentary focused on the 2015-16 festivals: “When Leviathan was released all the social media and mass media sources reacted very intensely. They started discussing that there was this place, Teriberka, where the film had been shot…and, look, the place is a real nightmare! And I posted on Facebook that it’s kind of strange, maybe we should go there then and just remove all that waste by ourselves”. After discussing the matter with other LavkaLavka members, Akimov came up with the idea of a festival called ‘Teriberka. New Life’ (Териберка. Новая жизнь) whose ultimate goal would be “…to breathe life into the village, and in case of success it would just be a model of social involvement, and that’s the point”. Besides the ‘social involvement’ (социальное неравнодушие) that was an acknowledged value of the LavkaLavka association, the festival became an effective means to advertise the brand itself, attract new customers, and not least of all, to create an event that would be pleasurable for the organizers themselves – thanks to the happy combination of beautiful Northern maritime landscapes and a diversified festival program. A typical festival during the 2015-17 seasons comprised several activity zones: a food court and a market selling handmade products; a sports zone; a music zone; and occasional discussion platforms where the future of depressed areas and Teriberka in particular were discussed by festival leaders, urban planners and tourism experts. The festivals usually took place in July-August, lasting two days and welcoming ever-growing numbers of visitors – from several hundred in the first year to almost 3,000 in 2017.

The initial concept of the festival was inspired by Leviathan and an impulse to change the depressed environment of a real/imagined village – to promise it ‘a new life’. However, from the very beginning the event was focused on attracting and entertaining the incoming guests (tourists), rather than getting to know the Teriberka community or engaging it through collaboration of any kind. Even the design of the festival – as well as the basic scenario for the revival – had been worked out far away from the shores of the Barents Sea. Regardless of whether LavkaLavka managers were more motivated by business interests or altruistic goals, the indifference they demonstrated towards the local population stemmed from the specific perception of a population living (staying) in a depressed territory as equally ‘depressed’, helpless, insignificant, invisible or even non-existent.

The LavkaLavka leaders reproduced the image of Teriberka as consisting of a unique pristine natural landscape alongside a decaying artificial environment. Nature had to be saved from people. This dichotomy left no space for the local population: for the LavkaLavka representatives who championed the ‘do it yourself’ ideology, the steady depression Teriberka suffered from indicated either an absence of a population or their inability to fight the depression. Framed as ‘a symbol of desolation and devastation’ (символ запустения и разрухи), Teriberka was regarded as a place where nothing ever happens because it does not have a significant community who can make anything significant happen. Thus the festival was meant to be the first ‘real’ event in an empty-as-uneventful and unoccupied space – ‘a clean set-up’ that would be filled with (new) life. The perceived invisibility and irrelevance of the community translated into refusing to integrate the locals into the decision-making process or in excluding them from the official festival program.

In addition to their invisibility, the local residents were also framed as incompetent and ‘economically and culturally off the grid’. The festival leaders associated themselves with the symbolic center of the country, namely Moscow. The qualities they ascribed to the population of Teriberka were automatically deduced from its remote position: for example, lack of local agency assumed lack of awareness about contemporary trends of economic development, such as event tourism. Therefore, one of the festival’s goals was to introduce the locals to the possibilities of tourism. During the 2017 festival, LavkaLavka organized ‘urbanist sessions’ with the aim to showcase the positive experiences of rural territories in Russia and worldwide who had turned to tourism. It is telling that the only locals who participated were those who could not avoid assisting the organizers.

Most strikingly, the festival masterminds openly acknowledged the irrelevance of the existing community and any local agenda for their revival project. During the 2016 festival, which involved some conflicts with those Teriberka residents responsible for the village infrastructure, one of the festival representatives claimed that Teriberka ‘does not belong to its population: their perspective is important but they do not have veto authority’[1]A comment made by the spokesman of the 2016 festival on 15 Aug 2016, retrieved from the festival’s official ‘VKontakte’ public social media page. to stand against the festival and the outcomes it might yield. Claiming the equal right of any Russian citizen – a Moscow resident as much as a Teriberka resident – to Teriberka as part of a national commons served to legitimize the entire project of Teriberka transformation, and led to the discursive (and actual[2]The actual, long-term effects of the festival will be discussed in a future publication.) stripping of locals’ right to resist the project. As long as the festival’s goals were represented as a means of ‘saving’ Teriberka from ‘depression’, the local perspective, especially the critical one, was deemed shortsighted and negligible.

The social qualities LavkaLavka ascribed to the Teriberka population both legitimized the creative intervention of Moscow enthusiasts in a remote rural environment and reinforced the popular conception of depression, remoteness and emptiness as characteristic of such environments. The notion of a ‘depressed territory’ frames the population as ‘derived’ from the territory, intrinsic to it, and imbued with all its defining characteristics. This linking of the territory and the population was noticed by the locals; as the head of the House of Culture in Teriberka put it: “It really insults us, the Teriberka residents, when they think of us as of…an appendix for the territory. Like, OK, somebody lives there. ‘Somebody’ stands for a conscious person. We are not those outcasts whom they always try to catch on camera and pass off as a local community”. It is noteworthy that under the ‘they’ the speaker meant different outsiders – regional authorities, tourists, journalists and of course, the festival leaders. The last group – while trying to solve the problems neglected by the state – ended up behaving just like the authorities (even fictional ones like in Leviathan). They ignored the local community and tried to impose their own plans for its transformation. Be that as it may, LavkaLavka has nevertheless set into motion a process of remaking Teriberka and its residents. Since 2015, the number of tourists and accommodation/catering facilities in Teriberka has grown, but along the way it is leaving Teriberka residents on the side of the road.

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the CC-BY (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International) licence, which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | A comment made by the spokesman of the 2016 festival on 15 Aug 2016, retrieved from the festival’s official ‘VKontakte’ public social media page. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The actual, long-term effects of the festival will be discussed in a future publication. |