On disintegration in a Russian company town

DOI: 10.60650/EMPTINESS-FY84-Q134

“Imagine life in a place that was encompassed by the weight of an industry and subject to a century of boom and bust, repeated mass migrations and returns, cultural destabilizations and displacements…” (Stewart 1996: 15)

“…picture how it oscillates widely between its dreams of order and prolific excesses, how it drifts in the flux of desire and condenses under its wright and force…” (ibid: 17)

On a sunny April afternoon in 2021, my colleague and I met with Grisha and Nata[1]My interlocutors here are referred to by their real names as they explicitly wished to be named in order to assert their agency. Translations of their words from Russian are mine. for an informal interview in the Kukisvumchorr district of Kirovsk,[2]The research was carried out within the framework of the Era.Net + Rus project ‘Enhancing liveability of small shrinking cities through co-creation’ funded by the Russian Fund for Basis … Continue reading an Arctic mining company town (hereafter, monogorod) in Murmansk region, Russia. We had not walked for very long when our interlocutors stopped in front of a ruined constructivist ‘Gornyak’ Palace of Culture. Abandoned in the 1990s, the building was severely damaged by fire in 2004 and the subsequent failed demolition attempt. However, it was still Kukisvumchorr’s dominant landmark standing on a hilltop overviewing the entire district. As we discussed the fate of the building, Grisha suddenly said: “I have just noticed how symbolic the PhosAgro tower is” – referring to the newly painted ventilation shaft of the PhosAgro apatite-nepheline mine behind the decaying former daycare building (see Fig. 1).

Kirovks (Khibinogorsk until 1934) was established in the late 1920s as a site for mining and processing apatite-nepheline ore, which is used to produce phosphorous fertilizers. The town, the first mine, and the processing plant were constructed simultaneously and rapidly in a greenfield – or, rather, in a ‘whitefield’ given the geographic context – in order to cater for the Soviet government’s need for resources during the rapid industrialization phase of Soviet modernity. During the Soviet era, the link between the industry and the city held strong. However, things changed after the collapse of state socialism, when transition to a Russian variant of neoliberalism and the accompanying private property regime began.

As suggested by scholars across various disciplines (e.g. Harvey 2006), neoliberalization of the global economy results in profoundly uneven spatial developments. While some places accumulate wealth, others are excluded from the circuits of capital flow or devalued by capital leading to their decay (e.g. Dzenovska 2020). However, patterns of decay may be complex, entangled, and ambiguous. Moreover, some might even push against the established theories of uneven spatial development. In Kirovsk, economic growth tightly coincides with the disruption of the social order and the built environment. This blog discusses the changing relations of production and social reproduction, as well as their underlying causes, drawing on longitudinal observations and a set of in-depth interviews in Kirovsk.

The industrial-urban nexus

In Russia, during state socialism the large-scale development of the High North was due to the need for natural resource extraction for industrialization (Josephson 2014). This involved establishing and maintaining control over a vast, sparsely populated area. Along with mines, opencasts, and scientific and military bases, new cities and towns were established where no permanent settlements had been before. Kirovsk was one such new town. It was founded against all odds amidst the snow and harsh winds of the Khibiny mountains for the purpose of extracting and processing apatite-nepheline ore. The Apatite Trust – owned by the state – was its so-called city-forming enterprise.

Constructing life around the industrial core of the city was a deliberate policy of the Soviet authorities, the basic rationale of urban planning and policymaking under state socialism (Collier 2011). Factories placed at the heart of cities became their new temples with industrial working rhythms and labour morality structuring social life. Any non-industrial economic activity in Soviet cities, such as tourism or services, was seen by the authorities as secondary. Thus, within the official Soviet discourse of urban development, cities and towns were foremost reduced to centres of industrial production with the formation of specific urban-industrial solidarities. Monogorods, such as Kirovsk, were the epitome of such development. Here, the provision of urban infrastructure, housing, public services and amenities (e.g. daycare and hospitals), as well as everyday life itself – were all tightly linked to the city-forming enterprise (Borges & Torres 2012).

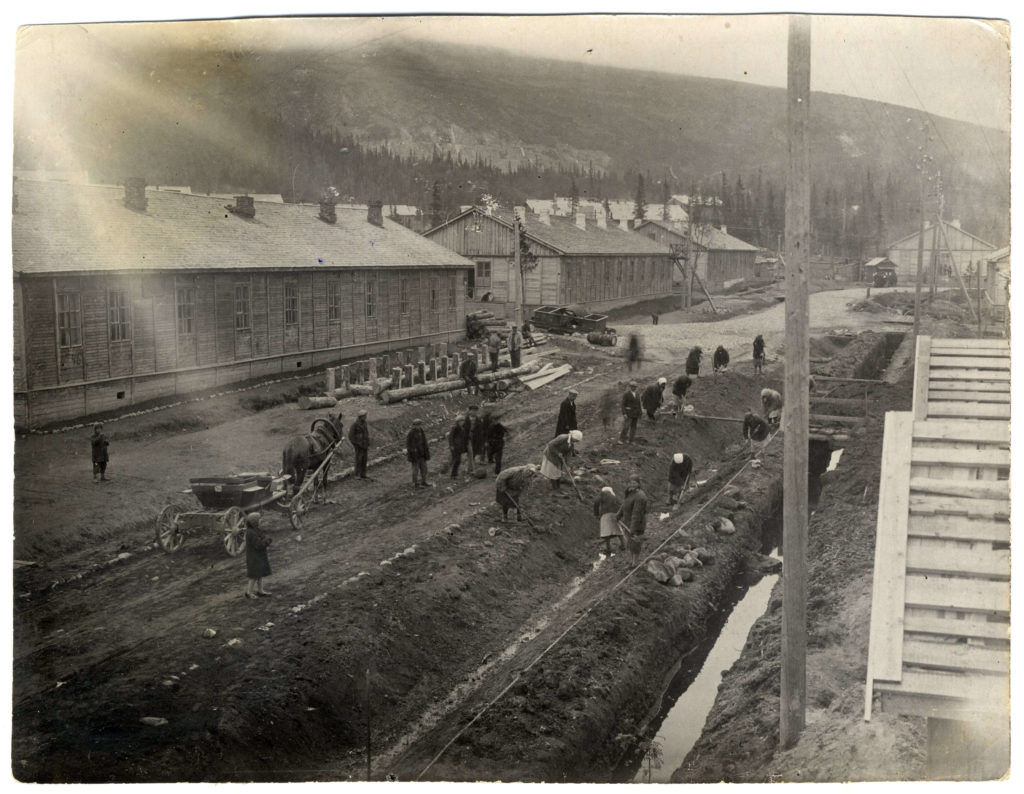

“This is how it was built from the very beginning…the whole town was a town where the mine workers lived…during the whole Soviet period, it was a very dense town-enterprise symbiosis. They were inseparable…” (Nata, April 2021) (see Figs. 2 and 3).

The formal structures of the town-enterprise unity nurtured tight, informal human relations around them. Grisha further illustrates Nata’s words with a story from his own childhood describing this link and grounding it in everyday experiences:

“Mid-1990s, I lived here with my mother and grandmother. One night in the summer my grandmother died, and my mother’s brother, my uncle, quickly came [to our place]…the ambulance arrived, doctors stated death…well, in the 1990s, nobody did anything, we had to transport her to the morgue ourselves or wait for a car to take the body out in the morning. So, he [Grisha’s uncle] just called someone he knew [from the enterprise], and a truck from the mine came, which was there on a night shift. Well, accordingly with the help of the truck the body was taken out to the morgue, we didn’t have to wait for 12 hours for the car from the city to arrive. It was just [an informal] call and the mine’s truck immediately replied and came. This was the norm – to be able to call someone you knew at the mine and get some help.”

Post-Soviet disintegration and the ‘loss of order’

The continuing consolidation of the urban-industrial nexus during the Soviet period lay the foundation for a severe crisis of monogorods after the collapse of state socialism. In monogorods, the crises that accompanied the transition from state socialism to capitalism was far beyond just economic hardship; rather, it brought about the collapse of the entire familiar social order.

Privatization of Apatite Trust occurred in the 1990s; later, in the 2010s it was taken over by the PJSC PhosAgro – one of the leading producers of phosphorus fertilizers in Russia and internationally. This led to the transfer of many ‘non-production’ enterprises’ assets and functions (e.g. the Palace of Culture, workers’ dormitories, responsibility for utilities) to the municipality. Kirovsk residents were suddenly deprived of the enterprise’s social guarantees, and former interactions between the town and the mine grew obsolete. Furthermore, the municipality’s ongoing fiscal crises defined the degradation of housing and utilities. The once-replete, seemingly manageable and predictable world of an Arctic monogorod suddenly became complex, turbulent, and precarious.

As noted by my interlocutors, the city and the enterprise were inseparable, functioning as a single organism. The enterprise was a common good ensuring work and providing welfare. It seemed to belong to every single resident, who referred to it as ‘our enterprise’, while its managers were merely administrators of this common good (Verdery 2003). Now the distance between the enterprise and the town is that much more obvious. It is being demarcated by fences, barbed wire, checkpoints, and cameras. Privatization brought about radical disintegration. The ‘non-productive’ assets and activities that were transferred to the town constituted a significant part of the enterprise’s value for Kirovsk residents – shared infrastructures and extensive networks of mutual support, the organization of both spaces of work and leisure. As noted by Kathrine Verdery (2003), socialism was a system based on values, both ethical and material, which were in many ways opposite of the values of capitalism. In this system, the Soviet enterprises were much more than just their production, whereas capitalist privatization reduced their essence to a profit-making machine, devaluing former solidarities and provoking nostalgia for a less precarious existence.

The indivisible monogorod run by the state-owned enterprise has now become a fuzzy assemblage merging different tiers and spheres of responsibility – the private and the public, with the public being further divided into the state, the state-departmental, the regional, and the municipal. This complexity defines a lack of coherence in governance that manifests itself in areas of decay and spaces of emptying which no one is able or willing to manage. The ‘Gornyak’ Palace of Culture is a case in point (see Figs. 4 and 5). The building formerly belonged to the Apatite Trust. After privatization of the enterprise, the ‘Gornyak’ Palace of Culture was transferred to the municipality. In 1993, all cultural activities were relocated to the ‘Apatite’ Palace of Culture (built in the mid-1950s) in the centre of Kirovsk, since it was problematic for the municipality to support both. Between 1993 and the early 2000s, the building was closed down until it was sold to an independent private investor who had plans for its redevelopment. But the fire in 2004 ruined it beyond repair. Subsequently, the investor tried to organize a demolition to free the land plot for other activities. But the walls turned out to be made from such an enduring mixture of concrete and local rock that several attempts at demolition have only led to one hole in the back wall. Since then, the investor has lost interest in the building. It has become a major ‘eyesore’ and a safety concern for the municipality. However, according to Russian legislation, the municipality cannot deal with or invest in private property, nor can it impose a penalty on the owner of an abandoned building unless there is conclusive proof of criminal activities taking place on the premises. Thus, in order for the town to pursue any action, it has to first initiate the process of de-privatization. This can last several years, involving a large number of resources and one or several court cases.

At some point there were (futile) expectations within the municipality that the issue might be resolved with the help and resources of PhosAgro. The expectations were supposedly fueled by the long history of enterprise-town interactions and the fact that the ‘Gornyak’ Palace of Culture did at some point belong to the enterprise. But PhosAgro seemed to distance itself from this issue altogether.

From city-forming to corporate social responsibility and exclusion

“Everything that belongs to PhosAgro is in order.” This phrase by Grisha (June, 2021) is the leitmotiv of my field in Kirovsk. It was repeated in various forms in various conversations and suggests that PhosAgro neglects the social sphere which the Soviet state had coupled with production. However, this is not entirely true. PhosAgro does have various corporative social programmes, introduces and supports many initiatives and facilities in Kirovsk – Khibiny airport, BigWood Ski resort, Tirvas sanatorium, and the local media hub being among the most major ones. One can spot corporate green-blue-white colours and the blue flower emblem of PhosAgro throughout the town marking its influence over its physical and symbolic space. Within Kirovsk there seems to be widespread opinion that these activities are a continuation of Soviet practices, expressions of the enterprise’s ‘city-forming’ functions. In part due to this association, there is a longing for a more comprehensive, historically contextualized engagement with the built environment and the social sphere.

However, rather than interpreting PhosAgro’s activities as being linked to the Soviet legacy, one should view them as a very contemporary response to the global trends defined by the need to secure the labour force and the Russian state’s enforced demand for political stability in monogorods since the crises in Pikalyovo in 2008-09.[3]The town of Pikalyovo, located in Leningrad region, is Russia’s best-known monogorod. In 2008-09, it underwent a severe economic crisis that brought the town into the media spotlight and led to an … Continue reading Pursuing a somewhat paternalistic path, PhosAgro strives to ensure the loyalty of its employees, diversify its own activities, and maintain good relations with the federal government. Whilst investing in some activities, spaces, and people, the company simultaneously excludes those who are not straightforwardly related to its agenda. A perfect illustration of this is the so-called PhosAgro classes – classes in Kirovsk public schools that are sponsored by the company. Within the schools, rooms allocated to PhosAgro classes are being provided with new furniture, IT equipment, and literature. Children who are not admitted to these classes, however, have no access to the resources and opportunities they provide. Thus, in expanding its business in depth and breadth and proliferating various aspects of the town’s everyday life, this globally operating company concurrently leaves behind ruination, exclusion, and ‘disorder’.

Places like Kirovsk are neither abandoned by capital nor disintegrated from the world economy. They are rather being gradually and selectively devalued. This devaluation leads to the destruction of space with a subsequent emergence of ‘unhealthy emptiness’ (Nata, April 2021) where voids mark specific changes and lacks (Vorbrugg 2019). Furthermore, by imposing fences and armed guards the company limits access by the town’s residents to formerly public and penetrable spaces (e.g. the square near the enterprises office in Kukusvumchorr district; strands along the privatized railroad and near the tunnels in the mountains), alienating them for the purpose of profitmaking. This alienation creates liminal zones that are neither recognized as the responsibility of the company, nor of the municipality which is reluctant or unable to care for them given the complexity of the national legislation.

Kirovsk vividly illustrates the ambiguity of capitalist development and the asymmetries of contemporary power dynamics. It is one of those localities that are being confronted with disruptions produced by global forces and powers structures beyond their control. The well-kept ventilation shaft appearing to sprout from a hole in the roof of an empty building mentioned in the Prologue (see also Fig. 1) is a perfect material manifestation of this reality – of the separation between production and social reproduction.

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the CC-BY (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International) licence, which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | My interlocutors here are referred to by their real names as they explicitly wished to be named in order to assert their agency. Translations of their words from Russian are mine. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The research was carried out within the framework of the Era.Net + Rus project ‘Enhancing liveability of small shrinking cities through co-creation’ funded by the Russian Fund for Basis Research (project number 20-55-76006 Эра_т). |

| ↑3 | The town of Pikalyovo, located in Leningrad region, is Russia’s best-known monogorod. In 2008-09, it underwent a severe economic crisis that brought the town into the media spotlight and led to an intervention by Prime Minister Vladimir Putin. This helped resolve the local crisis but the broader issue of dealing with monogorods remained, becoming a focus for several national programmes and priority projects in the following years. |