Experimental film. Part I.

DOI: 10.60650/EMPTINESS-XBG0-JM23

I started experimenting with film as both a medium for communicating stories and as a field method. I made this short film as part of a directing course I took at Pūces Akadēmija in Riga, Latvia. Participants were asked to create a short film with a twist ending. We were urged to learn the basics and then experiment. The basics involved: (1) developing a script with a clear narrative, preferably involving a central character with a desire, the frustration of that desire, and a resolution; (2) creating a storyboard; (3) following the storyboard during the shooting; and (4) editing. I did cover the basics, but not necessarily in that order.

I had shot some scenes before the course because at some points during fieldwork I felt like capturing things on film. I got particularly lucky with regard to access to the abandoned house featured in the film because I had made contact with the man who was buying up abandoned railway barracks in my field site in auctions held by the State Real Estate Agency (who had taken these buildings over from the Latvian Railway). He had bought the building that contained 4 separate apartments, but he hadn’t cleared those apartments yet as he had done with other buildings. He allowed me to enter the apartments (the doors were swinging in the wind), look around, and film. The apartment featured in the film had been abandoned after the death of the last resident – a woman by the name of Rozālija. Judging by the fact that the mirror in the bedroom was covered, Rozālija died in the apartment. Covering a mirror after a person dies in the house is a traditional practice in the area. According to one of the folk explanations given locally, the soul wishes to linger by looking at itself in the mirror, therefore the mirror has to be covered. Rozālija’s things were still in the apartment – a karakul coat, dresses, sheets, dishes, bills, and postcards. There were also some empty bottles on the floor, suggesting that someone had either partied or stayed briefly in the apartment following her death. There were curtains on all the windows. This is quite common in abandoned houses. The windows have curtains, and the doors are sometimes locked. Departing residents seem to want to keep strangers out, even if they aren’t planning to return. The man who bought this building bought it with the remains of previous lives.

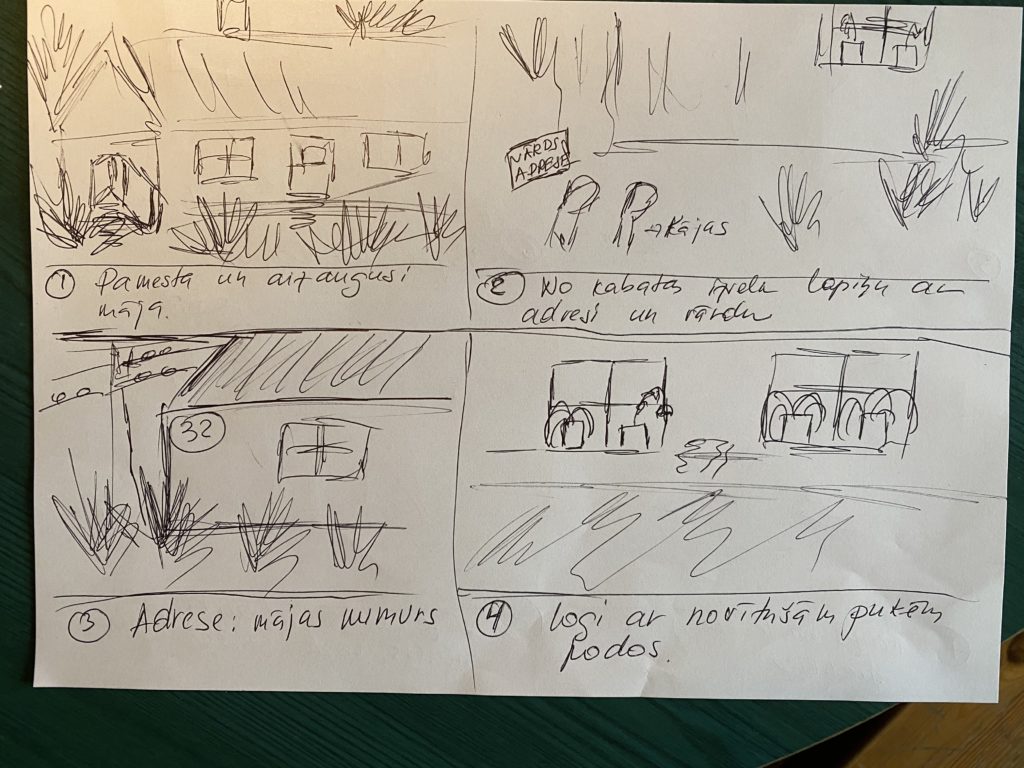

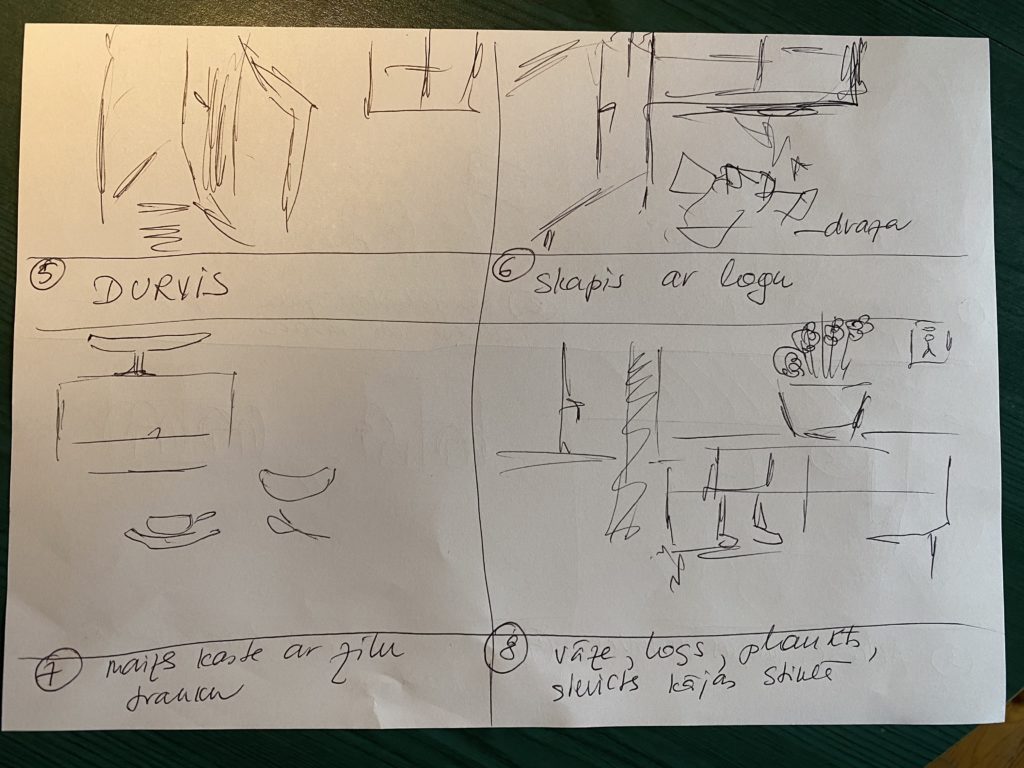

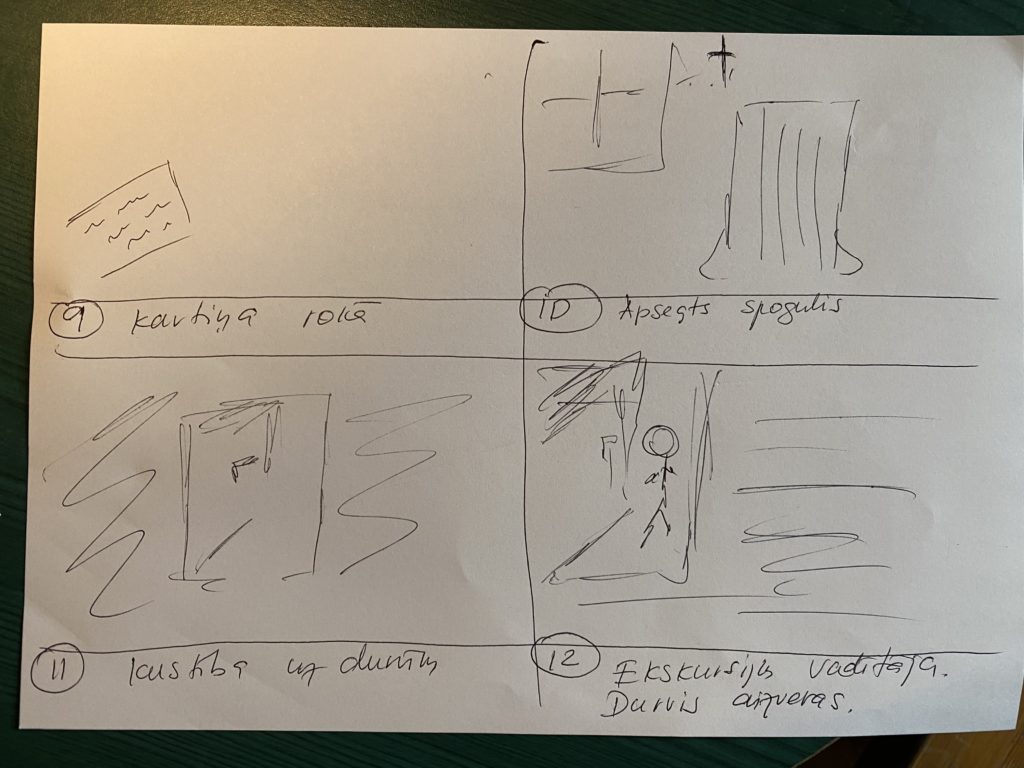

Having looked at the material I already had, I started developing the storyboard, lack of drawing skills notwithstanding (note that the final version of the film diverges slightly from the storyboard).

I wanted to conjure up a haunting sense of abandonment and then introduce a twist by suggesting that this was not only an abandoned house, but also a potential tourist exhibit. Ever since I started researching emptying villages and towns, colleagues and friends have pointed out a variety of “dark tourism” videos on the web. Young people in particular are fond of chasing ghosts – or their own dystopian futures, as historian Kate Brown suggested in a recent email exchange – in post-industrial landscapes. Some travel to abandoned villages and go through abandoned houses. I wanted to refer to the relationship between abandonment and tourism because tourism is often the only way of saving an emptying village that local officials can think of. In the absence of resources needed to properly renovate the “industrial heritage” of the railway, they show people ruins and invite them to imagine the village’s past glory. I wanted to connect tourism as the last utopia with the increasing attraction of ruined lives in the global tourist imaginary.

The film does not present an argument or a clear narrative. It conjures up a mood and suggests a variety of connections and interpretations. It is one layer of what, I hope, will be a multi-layered visual experiment. For now, it is part of an enjoyable learning process.

P.S. The opening shot is made while standing where railway tracks used to be. The building on the left is the former station warehouse.

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the CC-BY (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International) licence, which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.