Dispersed dispossession

This is an excerpt from the Introduction of Dispersed Dispossession. Collective Goods, Appropriation, and Agency in Rural Russia. An electronic version of the book is available open access. This excerpt is published here with the kind permission of the University of Georgia Press (© 2025 University of Georgia Press).

DOI (for this excerpt only): 10.60650/EMPTINESS-PKVM-6343

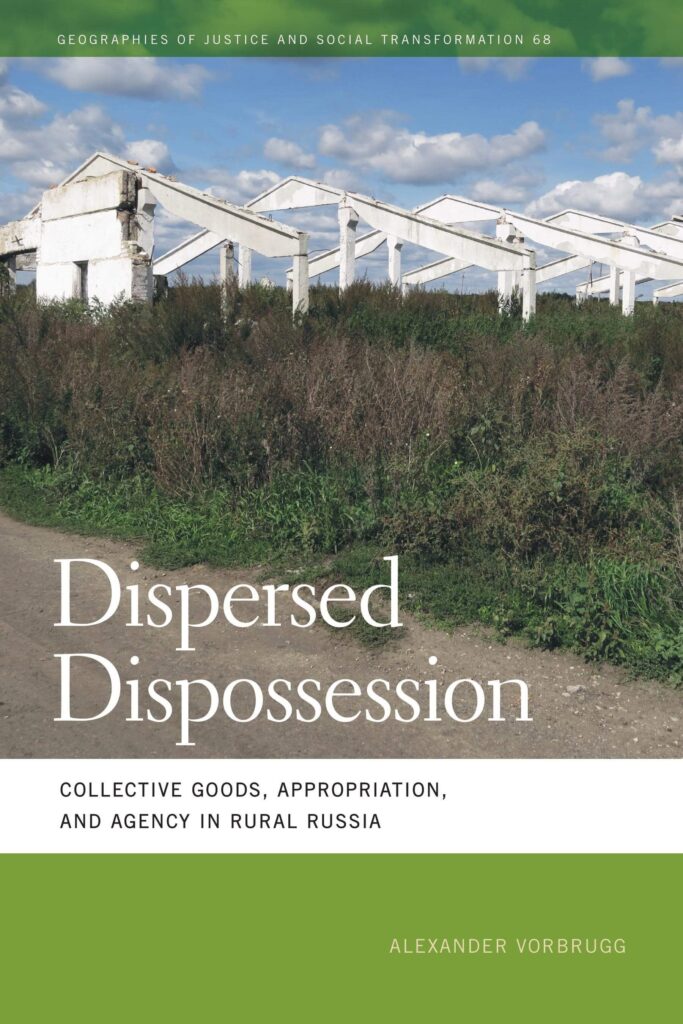

Dispersed Dispossession is an ethnographic study that delves into the paradoxes of agricultural revival and rural decline. It provides a nuanced analysis of rural change in Russia during the 2010s, a crucial and formative phase marked by the consolidation of giant agricultural companies, large land deals, soaring exports, and spectacular failures of investment projects. The book gives rare insights into the operations of large agricultural companies. It also reveals how the deterioration of material infrastructures, social arrangements, government and local supports, and collective goods erode the conditions of rural inhabitants’ wellbeing and agency. The following excerpt delves on the concept of 'dispersed dispossession' as an original and fruitful way to understand such losses as a form of dispossession.

The book greatly benefitted from exchange with the wonderful EMPTINESS team. I am grateful for this inspiration and feedback, and the opportunity to publish this preprint here.

Dispersal

Given the size of the companies, the pace of accumulation, and a massive concentration of agricultural assets in Russian agriculture today, the idea of dispersed dispossession may seem counterintuitive. Dispersion suggests diffusion rather than massive concentration, creeping rather than eventful transformation, and elusiveness rather than clear shifts. This tension, however, is essential for the argument put forward here and helpful to get to the subtler but also more systemic patterns of dispossession at the center of this study. To speak of dispersed dispossession is not to deny the magnitude of accumulation processes or the fact that some get rich while others become or remain poor. However, it refrains from taking the relation between these processes for granted and shows that a close analysis of dispossession may well open space for new questions and shed light on less-expected drivers and stakes and different temporalities.

One finds frequent though semi-conceptual uses of the notion ‘dispersed’ in various recent social-scientific studies that are often used to indicate conceptual and methodological challenges associated with a certain phenomena’s relative elusiveness, apparent randomness, or dispersion across time and space[…]. ‘Dispersal’ also reverberates with terms that are used as concepts in studies in postsocialist settings and relate to themes often voiced by inhabitants of the Russian countryside: disintegration, deterioration, discontinuity, decline, devaluation, deindustrialization, deeconomization, demodernization, decollectivization, depopulation, disorientation, or disenchantment. In Russian, there is a comparable cluster of terms, many of them with the prefixes ras/raz, indicating the undoing, taking or falling apart of things, a lack, a rupture, or regression. Thinking of them as a family of related terms is useful as it allows a clustering of related everyday and academic concepts – which we will encounter through the chapters – around a common theme to open new perspectives on the problem of dispersed dispossession.

Recursive crises, foreclosed futures: the temporalities of dispersed dispossession

Conditions for the types of accumulation and dispossession addressed in this study were shaped by context-specific crises that span the Soviet phase, the reform period, and contemporary hybrid or authoritarian state capitalism. They led, among other things, to a massive devaluation and multiscale disintegration of agriculture that were not a mere function of capitalist accumulation but provided a basis for it[…]. In our conversations, rural residents recalled poverty and mismanagement during Soviet times. They recalled how, in the early years of market reforms, new enterprises were unable to take off and old ones unable to carry on, pay wages, and continue production. They have seen the successive failures associated with state socialism and market reforms, each of them promising to undo the evils of the previous system. Politicians and investment companies often promise to fix the effects of past crises in one way or another, and they mostly fail to live up to any of these promises.

Such a sense of repeated and related crises is confirmed by analyses of the agrarian political economy[…]. The Soviet agrarian system was based on logics of abundance, expansion, extraction, and intensification and resulted in massive ecological deterioration and waste of resources (Josephson et al. 2013; Wengle 2022). Market reforms provided little means to clean up the mess created in Soviet times or alternatives for workers who became ‘superfluous’ as enterprises closed or were reorganized according to principles of efficiency[…].

In emphasizing the interlocking of crises, alienation, and dispossession across historic periods, the idea of dispersed dispossession does not presuppose ‘integrity’ – wholeness, intactness, authenticity, stability – as a reference base. Dispossession cannot always be attributed to one specific political system or period. Rather than identifying either state socialism or neoliberal capitalism as solely responsible for dispossession, the question to be investigated then becomes how it is rooted in and perpetuated through the succession of programs, regimes, and crises that caused a “multiplicity of destructions” (Gordillo 2014: 19) and created a condition in which dispossession is immanent[…]. [Post-Soviet] disintegration, and with it the “interstices of the old world and the new” (Dzenovska 2020: 23), turned out to be much more persistent than reformers had promised, and many expressed a sense that an old world had vanished and a promised new one failed to come about. The idea of dispersed dispossession implies that this is more than a mere sentiment, shedding light on how certain futures were and remained foreclosed to certain people[…].

Lived realities of disintegration: disorientation, disconnection, and disenchantment

If we imagine dispossession as a drama, the idea of dispersion impacts the entire scene – its duration, subject matter, roles, and context. If dispossession results from recurrent crises more than from single actions and events, this has consequences for the figure of ‘the dispossessed’, too. If the category should apply to all who live and act under these conditions, this would include large parts of entire generations. However, as the forms of and degrees to which people are affected depend on subject positions, such generic use of the category would make little sense. It is not necessary either. A focus on the mechanisms and effects of dispossession allows for acknowledging dispossession as a historic, and in this respect collective, experience without categorizing persons[…]. Dispersed dispossession does not always have a clear subject-object relation or manifest in clear dispossessive actions. Rather than focusing on isolated goods that can be held in private property, it is about collective goods, infrastructures, and further relations that support and sustain social and economic life, the upkeep of village and household economies. Dispersion evokes the image of a cloudy liquid or fog. This resonates with the persistent difficulties, described by many research participants, in navigating what appears to them as uncertain circumstances, recurrent and unpredictable changes, and unclear options[…]. This does not mean, of course, that dispersed dispossession took away all of people’s agency and vision, but it has impacted the conditions for developing agency and vision[…]. Dispossession that unfolds under such conditions is not of the kind that would be obvious to ‘the dispossessed’ or the analysts (Vorbrugg 2022), which is partly why dispersed dispossession requires a distinct conceptual vocabulary.

Appropriation

Historically and throughout the present, dispersed dispossession goes along with appropriation. It is well documented how many of the now wealthiest individuals and companies in Russia laid a basis for their power and fortunes by taking advantage of the ‘freeing up’ of cheap assets that resulted from the disintegration of the Soviet political economic system[…]. The rapid and massive growth of large agricultural companies would not have been possible without the rounds of crisis, devaluation, and disintegration that made land, agricultural enterprises, and labor abundant, freely available, and cheap[…].

Massive concentration notwithstanding, dispossession, as it is addressed by rural dwellers and conceptualized in this book, does not strictly follow, chronologically or causally, from companies’ land deals and enterprise takeovers in a narrow sense. Agricultural assets and labor in post-Soviet Russia were heavily devalued before capital showed any appetite for investing in it. Consequently, rural dwellers will accuse investing companies of exploiting existing deprivations rather than creating them. Many rural dwellers are not opposed to, and even wish for, a ‘good’ investor to revive villages and enterprises – a task many see as impossible to tackle without substantial state or company support. Disintegration and devaluation caused a fog that helps to conceal theft and created material conditions that make it easy to legitimize private investment and state interventions as corresponding with popular demands.

Under conditions unfavorable for smallholder farming for most, many rural dwellers heavily depend on large agricultural enterprises for employment. Agricultural enterprises, which often are the single significant employers in a village, can exploit this situation and sell poorly paid jobs as employment opportunities, as can politicians promising development to harvest votes. In this regard, dispersed dispossession created conditions to take from the rural deprived what is useful to the powerful: their land, their votes, their labor power, or even their lives when they are sent to war[…].

Reassembling

Dispersed dispossession erodes the conditions for many types of agency and results in increased vulnerability. Yet those who experience it are not passive victims of their circumstances. The chapters describe different ways of acting that respond to dispersed dispossession directly or that occur under conditions formed through it. Analogous to the family of de-/dis- terms that help characterize ‘dispersal’, a family of re- terms offers an appropriate entry point to understanding such agency: relating, repairing, recreating, recombining, reviving, regenerating, redeeming, restoring, reproducing, reinventing, recycling, and renewing[…]. We see it in attempts to maintain and revive reliable social contracts and material infrastructures, relations of support and care that have value in themselves and form the basis for individual and collective agency[…].

One may cluster these terms under the umbrella of (re)assembling, not to privilege assembling as a general approach to the social, but rather as a way of binding together three forms of agency central in this study. First, (re)assembling is a logical reaction to disintegration and dispersal and the forms of dispossession it implies. Where elements fall apart, they may be recombined and recomposed[…]. Second, assembling is as much about assemblages as it is about the agency that both underlies and emerges from it[…]. In this study, we will see the important role of forms of agency that aim at creating better conditions for further agency by strengthening infrastructures and collectives[…]. Third, assemblies of people, in a more traditional sense of the social, play a constitutive role for collective agency in this study. As with other infrastructural work, assembling people requires and creates and strengthens a basis for collective agency.

Images credit: Alexander Vorbrugg

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 licence (Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial Noderivatives 4.0 International), which permits sharing provided the original work is properly cited; but no derivatives, additional restrictions, or commercial uses are permitted under this license. This is an exception to our usual CC-BY policy as the article is a preprint excerpt of a forthcoming book.