Burning landscapes in Calabria

DOI: 10.60650/EMPTINESS-NB0D-XT05

A recent short film written by Luca Calvetta, E siamo i vostri figli (And we are your children), depicts the carbonised landscape of Calabria during this (past) summer of wildfires. It begins with an excerpt from a letter written in 1878 by a Calabrian migrant in South America: “Each departure is a fire. Each fire is the end of a world”. The passage hints of apocalyptic time. This summer, the landscape of Southern Italy – and Southern Europe, more generally – was marked by fires. Perhaps the only reason much of the world learned about this, however, was because the fires brushed against and consumed tourist destinations in Sicily and Greece, UNESCO world heritage sites among them. Yet, they were, and remain, terrifying realities for many. From Petrizzi, a town in Calabria where I was based for my research on the relations between people and land in Southern Italy since 1783, we anxiously watched fires carve through agricultural and forested terrain. We watched as helicopters and Canadair airplanes flew above, dropping sea water in attempts to extinguish the flames. At other moments, farmers gathered on their lands’ perimeters hoping to prevent damage as fires approached their crops. Sometimes, at night, the fires burned freely across once cultivated and now partially abandoned mountains, leaving mountainsides naked in the morning.

Petrizzi provides a lens to explore how landscapes materialise the ‘events’ that abbreviate historiography, forming coherent periods out of complex processes. Over the 20th century, officials connected the damage wrought by plant diseases (phylloxera in 1907), earthquakes (1947), floods and landslides (1935, 1951, 1973), and fires to a lack of maintenance due to the absence of farmers and workers. Reports in 1911 and 1912 tied uncontrollable wildfires to the “emigration [of labourers] to the Americas”. Stone walls fell into disrepair, grasses grew too long, and trees dropped their fruit to the ground. In 1935, floods destroyed roads and collapsed parts of the mountain adjacent to the town. In 1951, winter rains ravaged agricultural land, destroying over 200 houses and compelling the municipal administration to deliberate over relocating the entire town to the nearby ‘hamlet’ on formerly communal lands. Farmers and homeowners wrote countless letters to the local administration detailing damages. The letters convey the importance of land in the lives of those who remained, or who tried to do so. In 1959 legislation was passed which would aid families who had suffered material damages in floods caused by storms elsewhere on the Adriatic coast. This law enabled the release of assistance funds in Calabria, long after the departure of those who needed them was already visible in the town’s landscape. More destructive rains fell in 1973. From that moment until the present, the population declined by an average of around 12% annually; at present Petrizzi has around 1,000 registered inhabitants. But 1973 also saw the entry of a new structure of power in local politics, one that has attempted to erase itself from the records of this past (a point to which I will return).

The town’s history has long been shaped by the material conditions of its landscape. After the earthquake that rattled Calabria in 1783, people and land became entangled in a confrontation that refutes common narratives of modernisation. Power structures that had been under reform since the mid-18th century became unhinged. The slow dissolution of baronial estates and latifondi during the 19th century fed a land-purchasing ‘mania’, creating a new class of elite and disrupting traditional power relations. In 1818, Petrizzi’s municipal council noted that the privatisation of land and the increase in interest rates on repayment had driven many away from the town. This is far earlier than most accounts of ‘emigration’ begin. Later, attempting to maintain control over trade and commerce, landowners barred infrastructural projects such as plans to pave roads conjoining the town to the countryside and to surrounding towns. After national unification in 1861 they even claimed that roads would be used to foster political upheaval throughout the South. Peasants petitioned and occupied public lands (as well as other communal lands that had been privatised) to no avail. By the late 19th century, migrant departures established transnational networks that linked Petrizzi to Buenos Aires and Philadelphia. These networks would continue to expand.

Few historical studies locate their subjects in the places from which emigrants departed and when they do it is often only in relation to migrants residing elsewhere. The fires, in other words, have always burned in the background. Until the 1950s, most of Petrizzi’s landscape was cultivated. Over the course of the 20th century, these lands have seen a steady decrease in their usage by humans. Now, figs, olives, fichi d’India (prickly pear cactus), and grapevines grow wild amongst the oak brush and pines. Along with the decultivation of land, many surrounding towns have been depopulated, echoing a trend throughout Southern Europe. The stories that circulate in popular media – for example, about houses selling at heavily reduced rates in Spain, Italy and Greece – frame similar ’emptied’ towns as ghost towns, potential tourist havens or as locations that expose the dramatic material consequences of environmental transformation. Since the pandemic, new schemes for investment and ‘smart working’ from remote towns and villages have filled Italian news (even proposed as ‘south working’ by the Associazione per lo sviluppo dell’industria nel Mezzogiorno, SVIMEZ, 2020 report). Many of these schemes replicate urban-based labour markets and emphasise the aesthetic value of resettling in less-inhabited spaces without questioning the political-economic realities underpinning contemporary histories of ’emptied’ towns. In academic scholarship, on the other hand, the emptying of these towns is often described as an inevitable outcome of trajectories that trace back to early-modern urbanisation or to the 19th-century globalisation of mobility (see Jurgen Osterhammel’s seminal The Transformation of the World). In the historiography of migration, for example, emptied towns and villages appear as peripheries, attesting to an (almost hegemonic) approach which follows migrants and the impacts of migration out of and away from ‘hometowns’.

To write of ’emptied’ or depopulated towns and villages, however, is to focus teleologically on their pasts and to ignore the various trajectories of the present and of presents past. Furthermore, it is to obscure possible futures. Such depopulated – or, less populated – towns embody dense knots of historical time. They have not burnt into nonexistence. While they encompass those who have departed from them, they are not exclusively ‘emptied’ places in relation to departees. In exploring these trajectories, my own research focuses on connections between people and land in Southern Italy, on how seemingly ‘natural’ events such as fires, floods, earthquakes, and landslides punctuate regimes of migration, land ownership, bureaucratisation, and political alliance or membership. Such events did, in the past, propel historical time and intervene in unfolding processes. They continue to do so in the present. At the same time, they were part of protracted historical processes. This approach aims to embrace the multiplicity of time inscribed in landscapes, seeing their ‘emptiness’ as but one iteration of these material and discursive layers.

In the humanities and social sciences, scholars have begun to examine more critically the nexus of human and natural entanglements. While environmental history has a long genealogy, in rural contexts it tends to concentrate on agrarian political economy or large-scale industrialisation. Epistemological underpinnings in these bodies of scholarship gravitate towards strict divisions between ‘social’ (or humanistic) and ‘natural’ histories (this is less true in anthropology than it is in other disciplines). Emergent research on climate challenges such a divide and invites us to reassess historical time itself. The charred mountains of Southern Italy offer a suggestive landscape to interrogate this conceptual dichotomy. We might shift in the direction of a microhistorical analysis of relations (in the more expansive sense described in Marilyn Strathern’s Relations: An Anthropological Account) among individuals, communities, and the material landscapes they inhabit. These problematics raise crucial methodological questions: Through which archives and material landscapes might we access histories of depopulation? Which political and cultural practices are rendered visible or concealed by ‘natural’ events (such as fires)? How do such events function as vehicles for social and political transformation? How are emptying towns part of urban expansion, bureaucratisation, and other transregional movements? In what ways do the material histories that connect individuals, communities, and land challenge understandings of centres and peripheries?

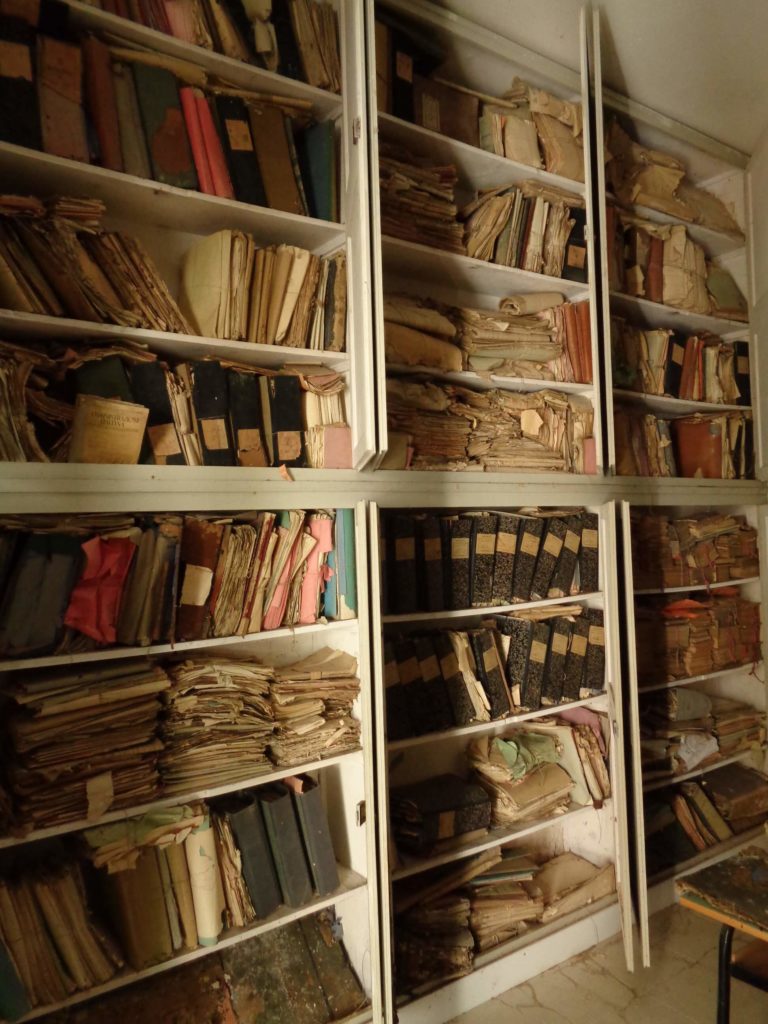

My concern with the ‘material’ is based on the possibility that abandoned archives and physical landscapes provide unique typologies of historical data. But what if these landscapes are razed by flames (both literal and metaphorical ones)? What if the departures – if indeed every departure is a fire – bring the destruction of archives of paper, dirt, and stone? What is left in and at emptied sites? What fills ‘emptied’ space? Ongoing research in Calabria suggests that the neglect of local archives, centres of documentation, repositories of shared knowledge, and other forms of material evidence has frequently been imposed or has arrived as a decision taken explicitly to disregard norms of an increasingly bureaucratic state. In some cases, neglect has come as a means to veil networks of power that aim to profit from the emptying of land (as in the case of post-1973 Petrizzi). There are instances throughout Calabria, for example, of illicit transfers of archival materials or archaeological artefacts (and some archaeologists have spent their careers fighting against these practices). At this conjuncture we can comprehend how individuals, communities, and the land are mutually constituted.

Returning to the fires. In recent years, a cooperative called ‘a Menzalora (a reference to the 19th-century granite measuring tool in the town’s piazza), has begun to cultivate abandoned land around Petrizzi. Their activities represent a desire to remain, to inscribe the landscape with meaning and value, and to make Petrizzi an inhabitable place. In some ways this connects with a wider movement to reinhabit rural spaces in Italy. The cooperative is locked, however, in a struggle for power against a relentless administration intent on progressing its own interests (‘cash and concrete’) over others. Today, when fires burn through the mountains, rumours spread about their origins and the interests of those who may have sparked them. Like the wind farms that have sprouted throughout Calabria in the past 15 years, the fires – for many – intimate political corruption and competing interests in control over land. Indeed, depopulation may have a carefully measured value underwriting it like those who relocate and disperse paper trails or others who assess stability and property value in the aftermath of earthquakes and floods.

In the corner of Petrizzi’s territory is a convent, commonly known as la Pietà because it once held one of Gagini’s statues. The convent was sold in 1814 (during the privatisation and land purchasing ‘mania’ mentioned above). In some way, it represents an embodiment of the changing social, political and environmental dynamics around Petrizzi. While it had been privatised – likely in the aftermath of the 1783 earthquake in which it too suffered damages – it was turned into a farm, with two peasant families residing on its premises with the owners. The convent’s territory included many acres of cultivable land, planted with trees and vines, and within its walls it once had its own stone mill. Until the 1950s, it functioned in this way. The family who owned it studied, trained, worked, and lived elsewhere; but the lands were worked by many others from the town. Eventually, a descendant of the original owner ‘returned’ with her husband, both trained architects, to restore the convent. It became a site at which children camped and families gathered for weddings, even as Petrizzi emptied into the 1980s, 1990s, and after the turn of the century. In some way, la Pietà is as much collective as it is private; it manifests the complex interconnection between individuals, communities, and the land that do not reduce to simple dichotomies or prefigured historical periodisation.

At the convent, another generation has ‘returned’ with the ambition to make the convent a space for individuals and communities to imagine and shape new futures on the land. In August 2021, fire struck the convent’s forested land, close to the municipality-owned forest and other cultivated lands. Some suspect that those fires were set intentionally: each year they burn through the same plots. Others speculate that the fires are part of a wider administration-led desire to clear space for investment projects which would profit from the land’s emptying. Fires are not mere consequences of environmental change, even if they are exacerbated by the climate crisis. They have been burning for a long time. The current residents of the convent intend to replant the forest, to remain. The cooperative, too, continues to chart paths through the abandoned overgrowth. Each fire might indeed be the end of a world. Yet, anthropologist Ernesto de Martino writes, “the end of ‘a world’ shouldn’t signify the end of ‘the world’ but rather the end of the world of tomorrow”. If each departure is a fire, what is the choice to remain or ‘return’? A reminder, perhaps, that these towns and villages are not empty?

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the CC-BY (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International) licence, which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.