An emptiness to fill

DOI: 10.60650/EMPTINESS-P9SM-2Q51

Montenegro. Njeguši. A small village. According to official data (e.g. recent census information on Wikipedia), there are fewer than 40 inhabitants. Hardly a village at all! It must have been the victim of the most severe process of emptying. It is almost empty already. And yet, it is still densely packed with life.

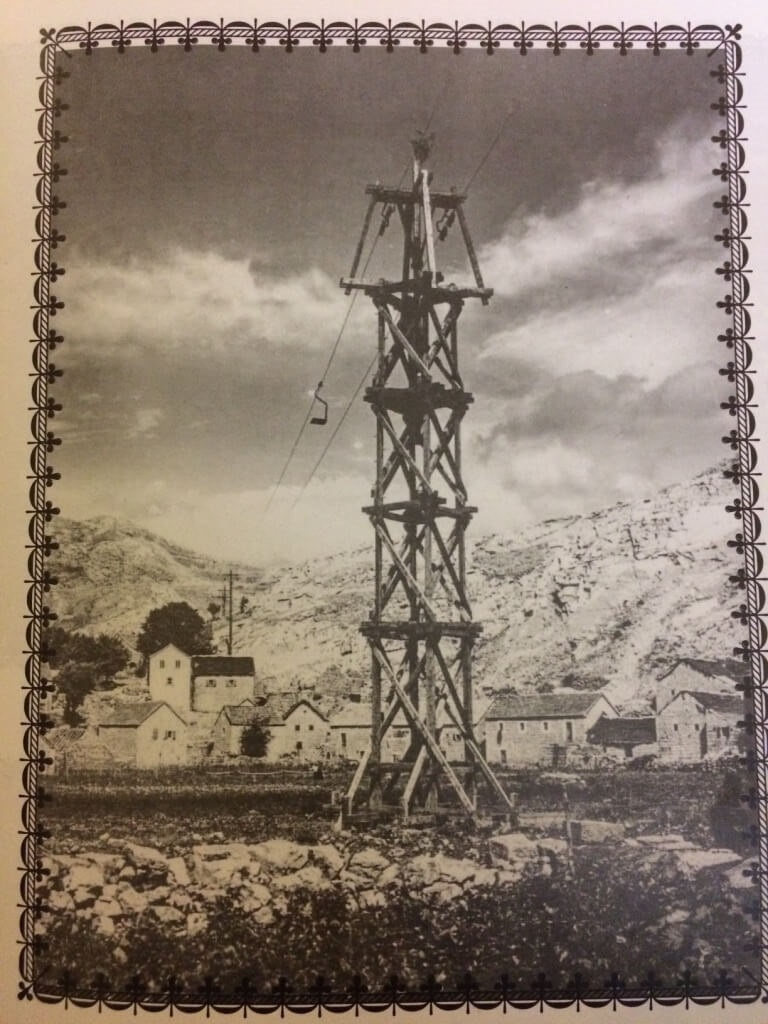

One of the first things we learned when we arrived there in 2017[1]During my fieldwork when I was accompanied by my wife Linda was about the cable car connecting the town of Kotor at the foot of the mountain to Njeguši 800 metres above, and then to Cetinje, the old capital of Montenegro several kilometres inland. I soon discovered the cable car (žičara) was no longer there. Only lonely concrete blocks where the cable car posts used to stand.

The posts, cable car, stations, and the cable had all been installed by the occupying Austro-Hungarian Army during World War I. The system worked until the end of their rule, after which essential metal parts were appropriated by local inhabitants, resulting in the whole operation grinding to a halt. The authorities attempted to recover the missing parts, advertising in local newspapers and appealing to citizens’ sense of patriotic duty. But the citizens apparently felt otherwise, and the recovery attempt failed. Žičara was dismantled in the 1920s.

Žičara nevertheless seemed to be one of the most important elements of the landscape. Everyone asked if we’d been told about it. It seemed that almost everyone we talked to had personally seen or even ridden on the car (žičara was in fact suitable only for transporting cargo, not people).

There were many ruined houses in Njeguši. Among those not ruined, most were empty – abandoned or only rarely inhabited by people coming perhaps for a short while during the summer season. Njeguši actually comprises 12 smaller villages, one of which is completely abandoned while another, Žanjev Do – possessing a spectacular view over the fjord-like bay of Kotor – is only inhabited during the summer. Njeguši also has 12 churches, of which even the few well-kept ones operate only on very special occasions or not at all, and 14 restaurants open during the tourist season.

Yet among all this emptiness we were rarely alone.

“Do you know that you live in the house of Guvernadur Radonjić?” asked the host of the small house we rented during the first part of my fieldwork. The house seemed empty. Even the stove had been removed, leaving only a tin-covered hole where the chimney once used to be. No, we did not know anything about Guvernadur (Governor) Radonjić, but apparently the house and its small concrete car park at the front had once witnessed dramatic events of state importance.

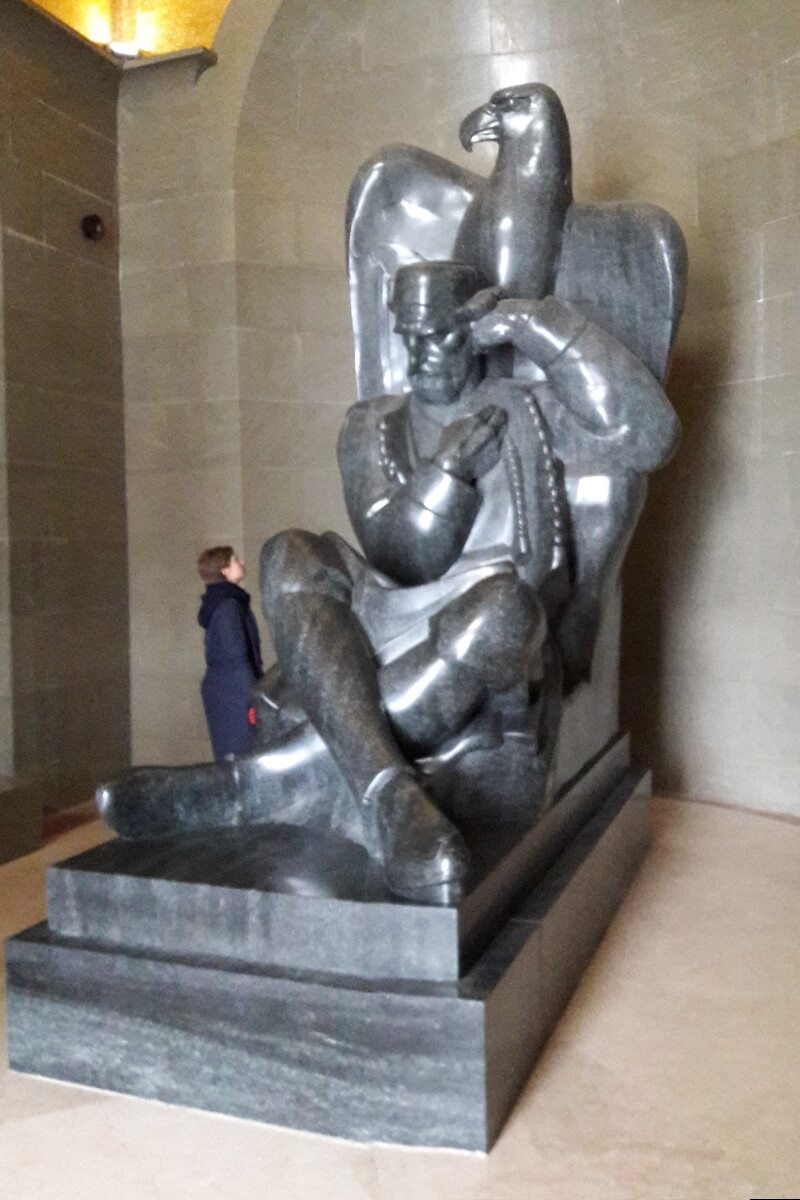

Guvernadur Radonjić was an ancestor of our host’s. The 19th-century Governor had opposed Prince-Bishop Petar II Petrovič-Njegoš (often simply called Njegoš) of Montenegro. In short: the Governor lost, was exiled to Kotor, and later imprisoned and died; many of his relatives fled, too. The victorious Prince-Bishop Njegoš’s mausoleum now sits at the mountain top that peaks over the village and is an international tourist attraction. It is a spectacular site, with a 30-tonne black granite sculpture erected by atheist Communists during the Socialist regime.

Descendants of Njegoš’s Petrovič families and some other relatives still live in the village. It would be a mistake to imagine no one cares about this long-past historical grudge. People care not only about the relatively modern žičara, but they care even more so about what happened to the Governor and Prince-Bishop back in the early 1800s.

When the Governor’s descendants wanted to inaugurate a small church they had fully restored by investing their own effort and money, the police appeared with a letter from the competing Orthodox Church faction who claimed that they, too, wanted to hold an event there on the very same day at the very same time. The opposition faction did not in fact arrive, but the event was ruined anyway.

Where the descendants of the Petrovići family live in the village, there are several important buildings. Most are empty and in varying degree of disrepair. For instance, the country house of the last and only king of Montenegro, King Nikola I; a house of his uncle’s; and the local church. A building that was probably once among the smallest in this group had become a museum. Njegoš, King Nikola, and many other important men had been born there, and for some time had lived the simple, rustic Montenegrin life of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Next to this group of buildings were spectacular ruins of the hotel built in the last years of Socialist Yugoslavia. “Hotel of the category ‘B’!” my neighbour Tomo proudly emphasised. He had worked in the hotel prior to its closure. “That was a time!” Tomo nostalgically recounted.

And then there was the school with the ‘phantom guard’. There used to be two schools in Njeguši, but both were closed now. There was only one under-18 child in the village and his family arrived after the schools had closed. But there was always somebody doing something on the upper floor of one of the school buildings. Every evenings when we passed by, we would see a light there. Sometime later we learned it was the office of the local registrar’s. This woman, who otherwise worked in her farm and tended animals, sold us some home-made sausages.

“So it’s you who goes to the office every night?” I asked. “No, no”, she said. “It is only for protection – I leave the light on so that the hooligans would think that somebody is there and would not smash the windows.” So, the office was guarded by a ‘phantom guard’, conjured by the registrar switching on the light.

The restaurants also benefitted from the occasional help of other ‘phantoms’: pigs. One of the village’s main industries is production of the local smoked ham (pršut), yielding about 100,000 hams a year. Each pig has two hind legs, and each leg gives one ham. So to sustain the business, about 50,000 pigs a year are needed. But all the meat is actually imported from across Europe during the autumn when the pršut production cycle stars.

After being after being treated to this delicacy in one of the restaurants, a naïve tourist (tourists, of course, are always naïve!) once wondered where the inhabitants of Njeguši kept all their pigs – as he could see none. The local waiter smiled and replied without hesitation: “We keep them in mountain pastures because, as you can imagine, pig farms smell. We would not want them here.” Needless to say, there were no pig farms in the legendary summer pastures – places that used to be busy but were now almost completely abandoned. Only one or two local villagers still kept some animals there, but never any pigs.

So the emptiness here was not empty. Emptiness and emptying in Njeguši created a space to be creatively and actively filled by whatever the villagers could imagine. There was the cable car zipping across the empty sky. There were the magnificent ancestors who made life so much more meaningful for their descendants. There were churches and schools and other buildings that were all apparently empty (except the restaurants that were kept busy with tourists). And the hoards of ‘phantom’ pigs roaming the vast mountain pastures.

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the CC-BY (Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International) licence, which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | During my fieldwork when I was accompanied by my wife Linda |

|---|